Objects of Transformation

Jacob Todd Broussard in Conversation with Robert Storr

Two painters meet in art school. They could not be more different: in age, in background, in social experience, in sexuality. Yet each is entirely at home in his own type and degree of difference. In parallel proportions both are misfits in their hereditary milieux. So they hit it off and start a conversation. Both read widely but off the syllabus. Both are fully, unselfconsciously Francophone. Moreover – and more importantly - they have in common a love of their medium in all its most “painterly” aspects, and a penchant for the less traveled roads and the underknown masters of their tradition. Their taste in music runs in the same digressive directions. That is to say away from “mainstream” Pop, Rock and Hip Hop toward Country, Roots and Cajun Music. Significantly the father of the younger of the two men plays the latter professionally in clubs and roadhouses in Louisiana Bayou Country and his son has painted posters and album covers as subject matter. The older man has spent time in New Orleans and couldn’t get enough of it. Eventually, the younger man, who was a student of the other, graduated. Not long after his professor retired and was liberated from the constraints of being “older and wiser.” Their conversation has continued, deepened and improved.

Robert Storr – Brooklyn, June 2023

Robert Storr: The color in your work is oddly and enticingly - even suggestively - penumbral despite its chromatic intensity. Have I got that right? Is that by design or not?

Jacob Todd Broussard: I haven’t thought of that descriptor (penumbral) before regarding the color of the paintings but I think that is the apt word. I love that, how it is suggestive of an eclipsing of light. The term “color story” keeps cropping up in my mind when I plan out the paintings: what color story would I like to tell? This is maybe unnecessary, but my process includes picking the specific colors from color aid paper, then mixing my color in batches before I begin to paint so that I have everything I need. Once I start, it becomes a game of surprising myself really by getting from one color to the next, a value shift in a chromatically intense color to a warm or cool shadow. Those shifts are intentional, I believe that they have the effect of creating an atmosphere that I am after in the paintings.

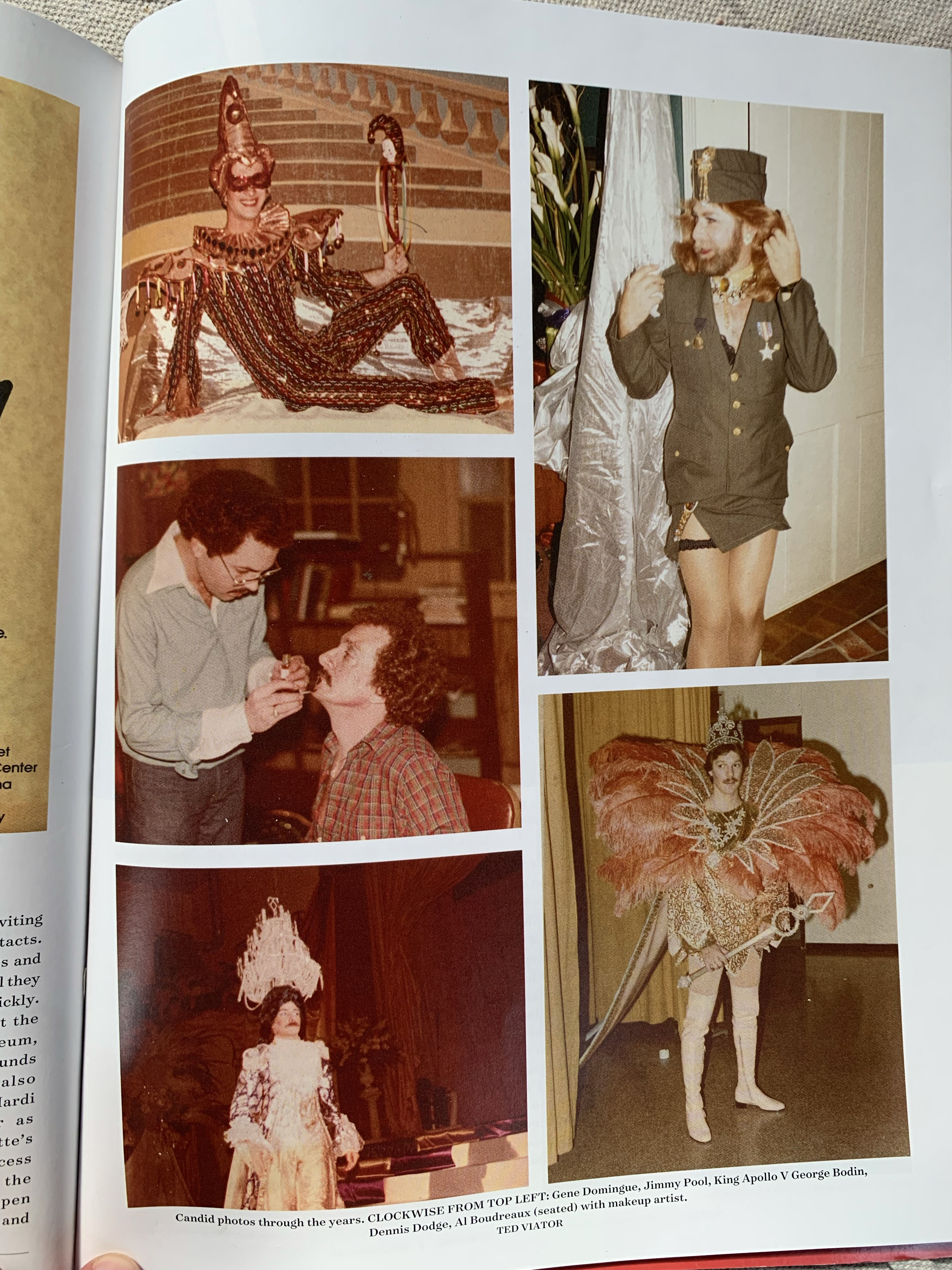

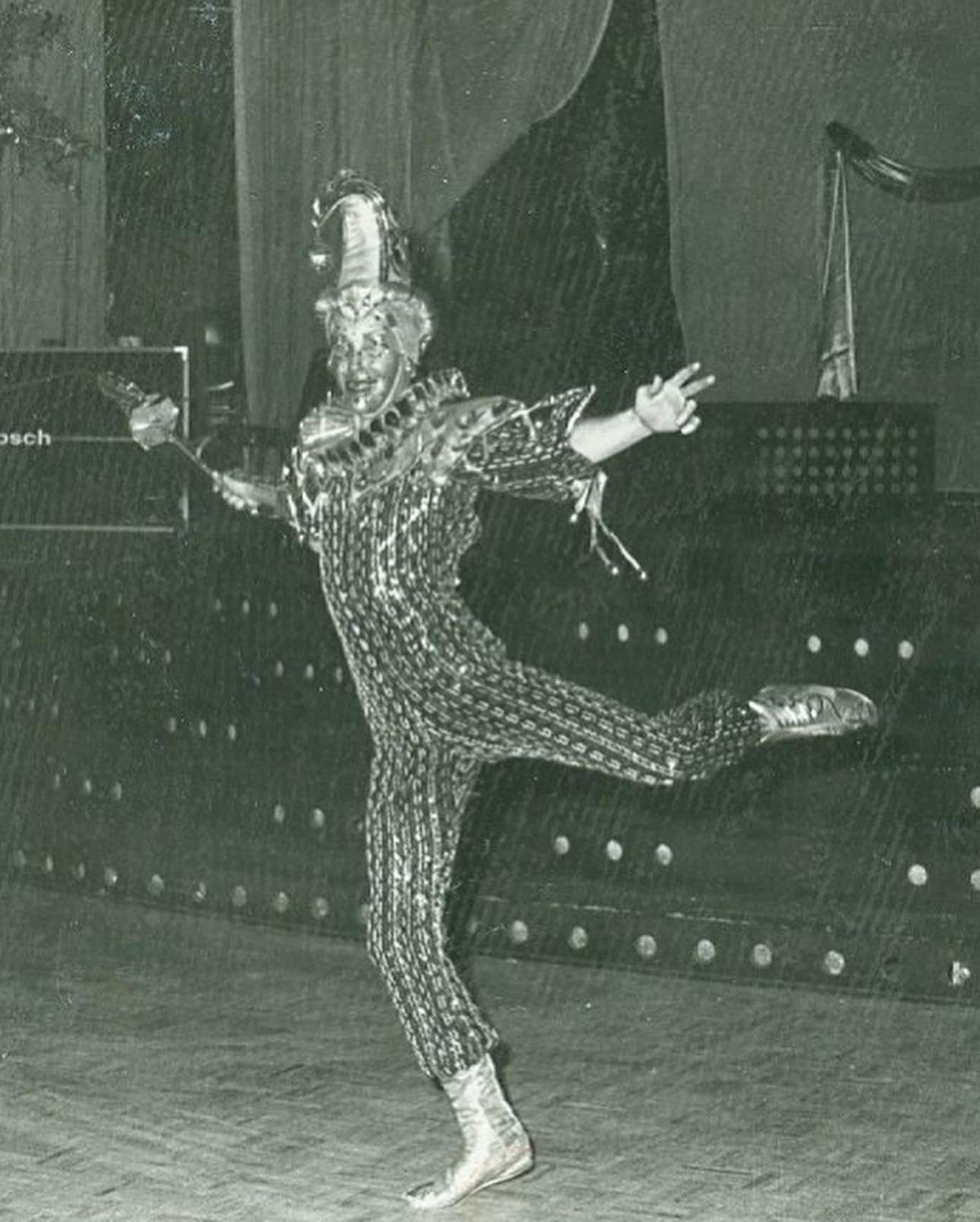

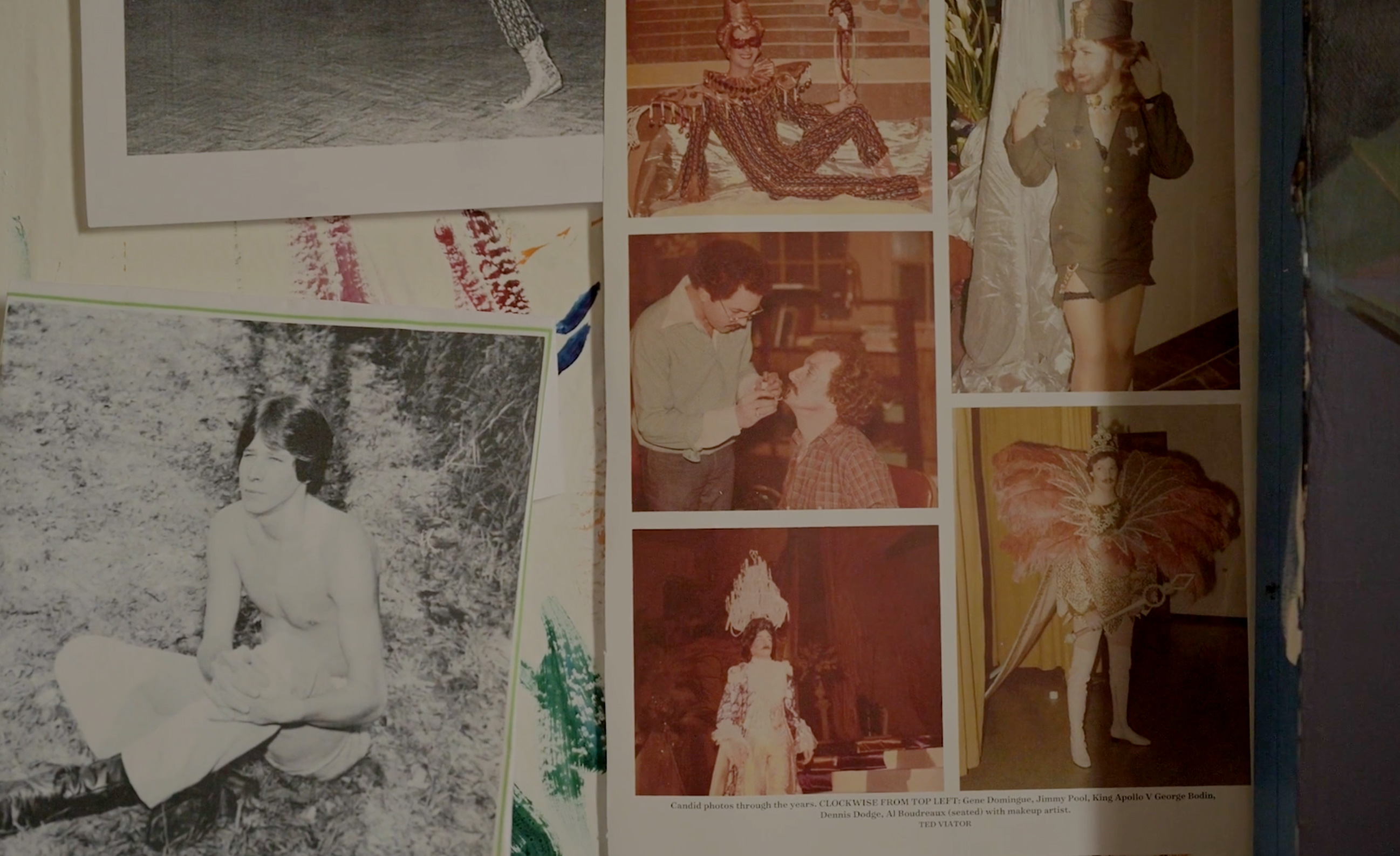

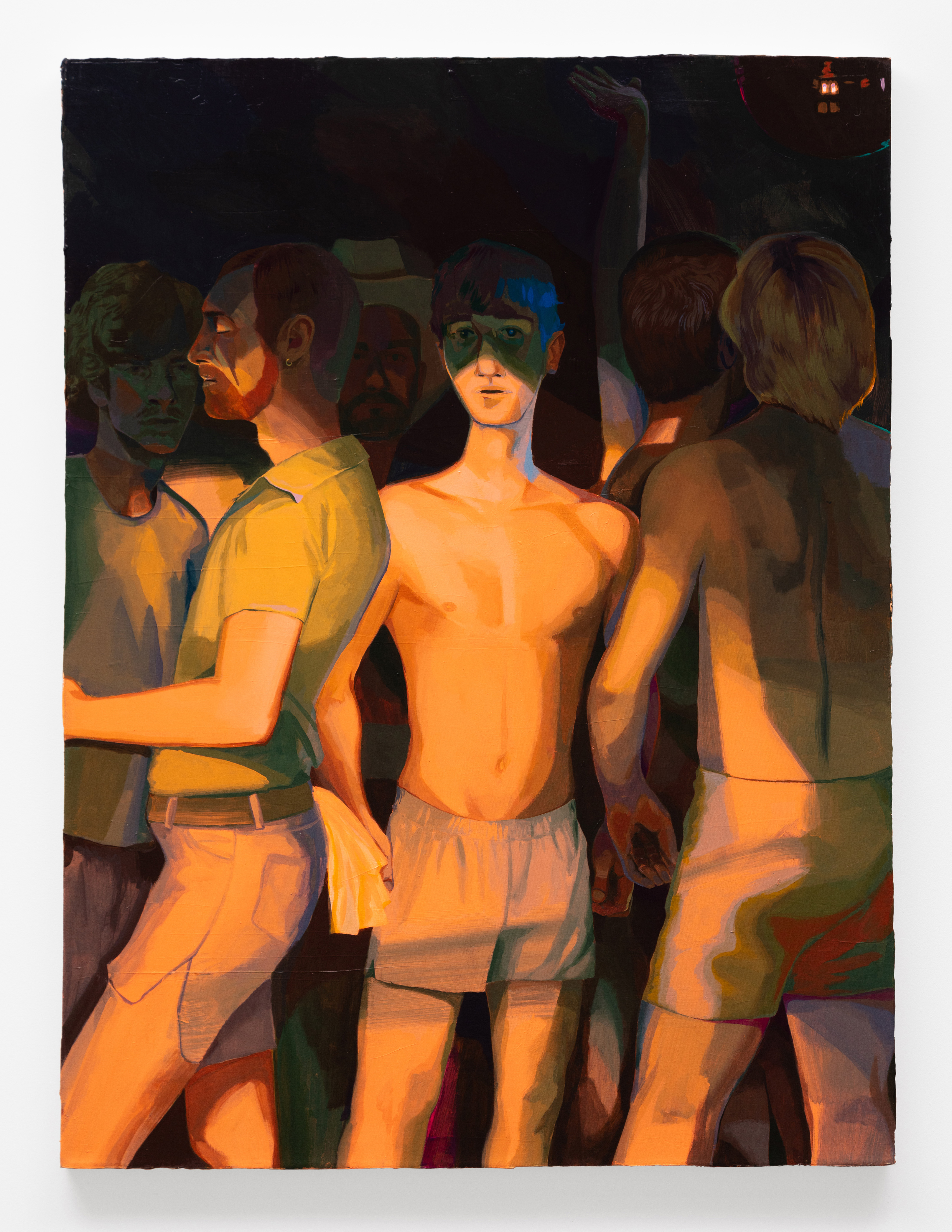

Robert Storr: Clearly there is an element of magic at work in several of these pictures. The feral dog prowling the torso of the flat chested boy in one, a man dancing inscribed over the nose and brow of another is second. In the latter instance, if I understand correctly, the source photo is of your cousin Gene who was part of a gay Mardi Gras krewe. In fact, he resembles a chorus boy from the Red Shoes. Could you say something about the tradition involved here and about Gene and your relationship to him? How did you become aware of him? Does his existence inform or in any way frame your way of being a gay man in the Deep South in the Age of Trump and Desantis?

Jacob Todd Broussard: I became aware of Gene by accident, really. I had peripherally known of him just as a fellow gay man or odd duck in my family, not really having access to him being that he passed away in 2000 and we never met. I’m originally from South Louisiana and I hail from a long lineage of Cajun french blood on both sides of my family. A couple years back, I heard about the Mystic Krewe of Apollo de Lafayette and its legacy through a magazine article. For context, a krewe is an organization that stages an event, parade, or ball in celebration of Mardi Gras, specifically associated with South Louisiana. The Mystic Krewe of Apollo de Lafayette is the largest and longest held gay krewe in Louisiana. The krewe originated in New Orleans in the 60s but then moved to Lafayette (my hometown) in the late 70s. Each year, the krewe throws a ball which follows the decided theme of that particular year. The ball was a social event specifically for gay men of a particular community to come together in private and allow themselves to be whatever they wanted for an evening. Carnival is a temporal device used to flip all the rules i.e. the man can become the woman, the peasant can become the king. The ball consisted of a royal court with local community members yearly crowned king and queen (the queen historically being a man in full drag). It’s also a form of queerness that truly holds its own vernacular by existing outside of the monoculture. There’s a particular freedom it embodies, not having to prescribe to the frameworks of gay culture that exist in gay centers along the east and west coast. That, I believe, to be particularly Southern and that it could have only metastasized in the murky swamps.

I think that Cajuns are culturally queer in a broad sense... Historically, they've been seen as outcasts within their own region, speaking a strange guttural French, practicing superstitious pagan-Catholic religious rituals, and producing a vernacular that was very unfamiliar to the American ideal.

So there’s a doubling that happens. There are traces of those vernaculars today, but much has been Americanized in the last century.

At the time, I was working on these hand drawn posters of a real gay bar that existed in Lafayette which I couldn’t find any digital traces for at all. So the gap in the archive provided an opportunity to imagine. I made these posters for imagined events and I was sourcing imagery from various places, thinking broadly about the krewe and there being some possible crossover. I happened across these incredible images of the members of Apollo and decided to use one of the figures for a drawing. It wasn’t until an aunt informed me that the masked reveler was our cousin Gene Domingue, a key member in the krewe. What are the chances that I’d choose that image and it would be a blood relative. The found photo, through an act of transformation, had a deep resonance that I couldn’t just place as “coincidence”, there was a reason I was drawn to that image in particular.

There is a sacrificing of a realism in order to gain a different understanding of something.

I’ve always been drawn to Cajun folklore of my childhood, ghost stories, boogeyman tales, swamp lights which denaturalize a subject and make it supernatural. In a way, Gene occupies a similar space of the folkloric, a larger than life persona in my own mind. And painting has the ability of being counterfactual, of occasioning a paranormal event on its own. Or so I’d like to believe. In our contemporary moment, we’re bearing witness to a political movement that is systematically attempting to erase queer folks, specifically targeting trans people and completely deflecting and distracting from the actual problems, all under the guise of protecting children which is complete bullshit. It all feels like a last ditch effort on the right, and final stands are always bloody and ruthless. I think Gene is a reminder to myself that queer people have always been around and will always be around, a “Don’t Say Gay” policy won’t prevent a child from becoming who they are. Will it make their grappling of self more difficult? Most certainly, and that’s disturbing…but queer folks are resourceful and always use what they got, much like the resourcefulness of the krewe during a very different time. That’s all to say, these things must be opposed with great force.

I think Gene provides a shape of alterity that I'm drawn to and how I relate to my own place in the world–a focus on becoming rather than being.

To become Other than what I’ve been and honoring that spirit in light of oppositional forces. Easier said than done of course, but also refocusing on community and policy for actual systematic change.

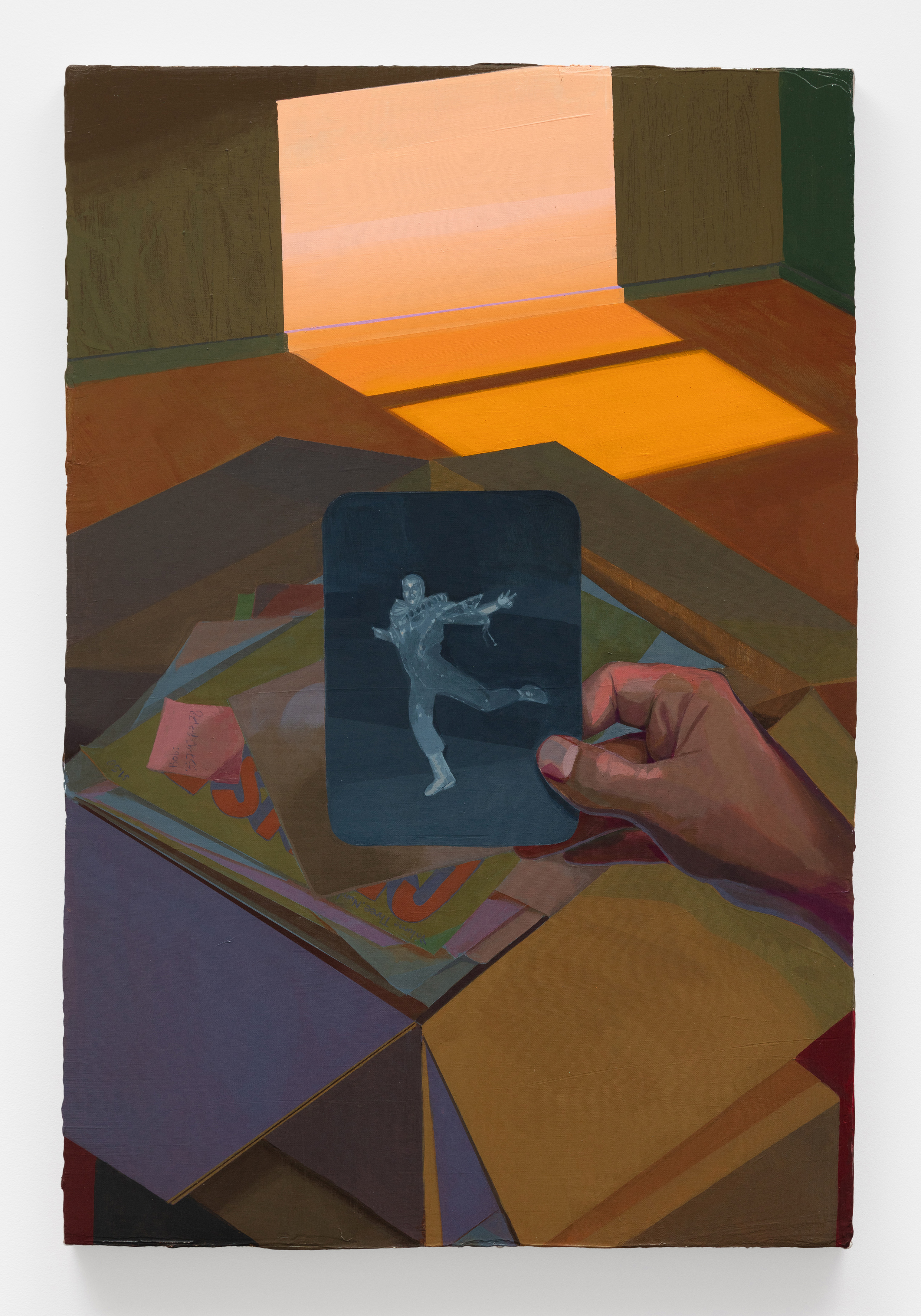

Robert Storr: Where an artist starts making a work is the crucial decision in its creation. Your paintings result from the knitting together of many parts, most recently those include obviously photographic elements that appear without recourse to any “photorealistic” illusionism on your part. Could you say something about how an image takes shape in your work? Does it come to you all at once or do you piece it together from scraps you’ve remembered? Or from things you observed and made notes on? Are these constructed memories, or ones that flash in your mind’s eye and are then fleshed out?

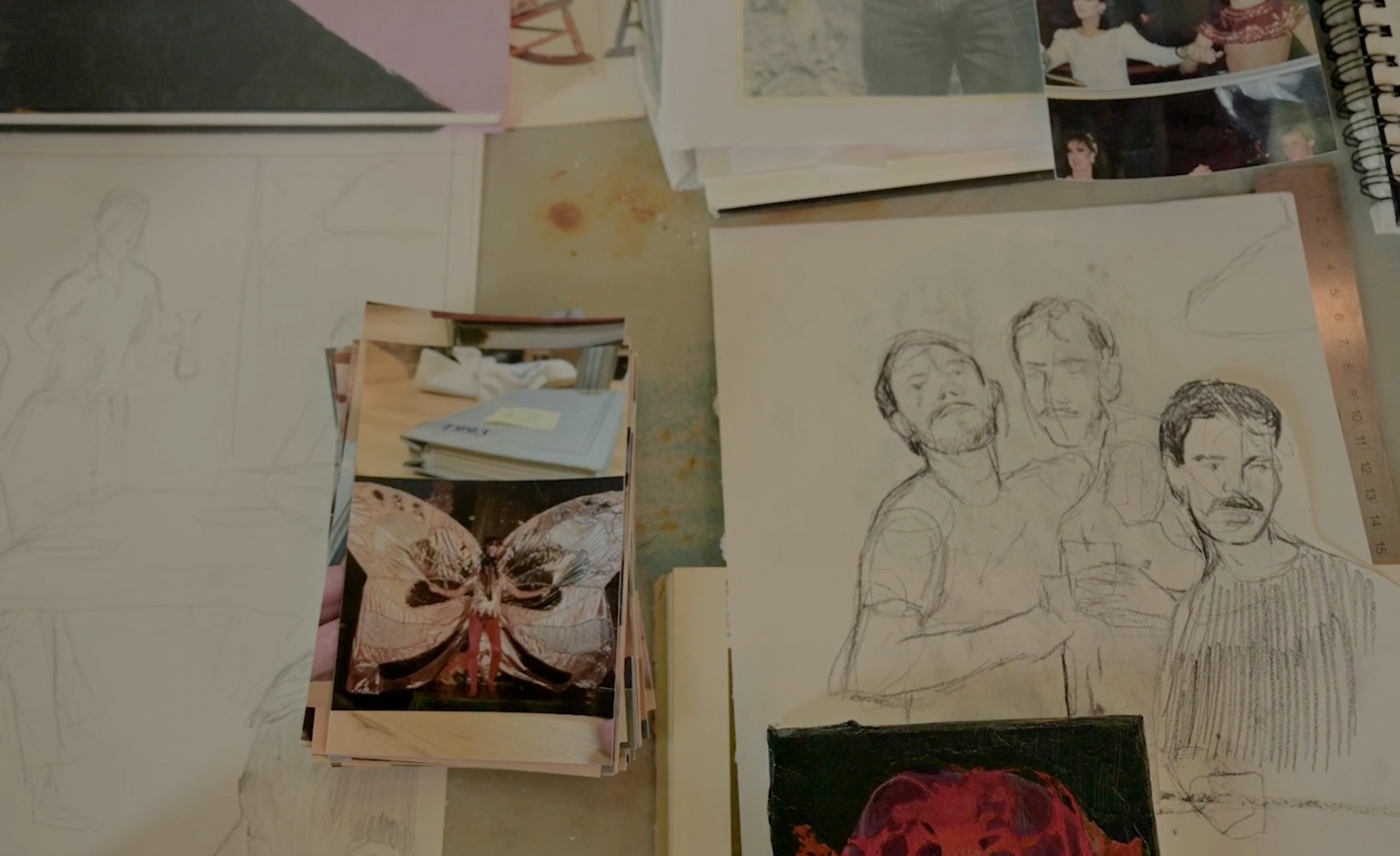

Jacob Todd Broussard: I’ve been thinking of starting points and something you actually shared with me during a studio visit years ago in grad school: we were talking about beginnings and how the painter Jess pulled from ready-made images, you mentioned that he would pull a reference image and denaturalize it through its materiality and color. That stuck with me, and although it’s rather obvious and we know this, the painting doesn’t have to be a completely invented image where everything is autonomous or siloed from the mind of the artist. That level of invention is overwhelming to me. So I like to think of the paintings as sites to stage things I’m drawn to, from images or things I’ve collected that have resonance. Of course, with these paintings, there is a familial connection with Gene as a starting point so that implicates the work in a directly personal way, the stakes feel higher. However, with that comes the gaps of memory, time working its steady hand on all things. I didn’t know Gene personally and there’s little I could find about who he really was as a person.

In a way, there was this dance of closeness and distance to this enigma of a person who I could never really know.

The template he provided became a starting point to imagine who this person might have been while also examining myself. There are only three images I have of Gene–and in each one he is wearing a mask. The mask reveals as much as it conceals, so that dynamic feels like a point of interest. The paintings include traces of things which I imagine this person collecting or encountering, points of interest, most of them are actual totems of memorabilia that I personally own. Some of the paintings are scenes of an unboxing of an archive by a distant relative, an archive that includes a sense of longing or feeling. The act of research (or re-searching, of searching again) felt resonant. I love a research project but I also know there are so many more efficient ways to research family history and to produce something like a family tree or an archive. But that all feels too sterile, it becomes about reporting. I want to ponder on feeling more and painting becomes a site for those two things to come together.

Can painting become a counterfactual simulation for me to run a hypothesis on who this person might have been or the similarities between us?

One source of visual imagery is this facebook group I’m a part of; an older generation of gay men from my hometown have collectively uploaded personal photographs from the 70s to the 90s, lots of photos of preparties taking place in someone’s living room before a night out on the town. These were members of Gene’s community and I was lucky enough to find one photo of him in these archives. I’ve also been looking at the drawings of Harry Bush, a relatively unknown erotica artist and painter who published a number of illustrations in Physique Pictorial; some of his figures have served as compositional armatures for the paintings. There’s something about the forgotten or the overlooked that I’m inherently drawn to, the “scrap” as you mentioned, a form of queerness that has been forgotten by the monoculture which embodies a certain loneliness. Objects that appear in the paintings (Patrick Cowley records, old photos, a Forrest Bess painting, ephemera, paperbacks) are objects that I consider of significance to me, objects of transformation. It’s a piecing together of things to make the space between longing for the not-yet-experienced and for what’s already lost smaller. Writer Jeremy Altheron Lin has this great line about queer history being a palimpsest of what ifs.

Robert Storr: Your figures are very carefully rendered in your drawings but essentially flat in the paintings. What is the relation between the readily legible volume of the former and the relative lack of bulk in the latter.

Jacob Todd Broussard: There are two things that come to mind. The paintings depict interior scenes that contain frames or open into other spaces somewhere in the picture plane. I knew I wanted to make interiorities with these paintings and move away from landscape. The way that light travels across a wall of an interior (whether from a lamp or from a window) and defines space is a color concern. I feel like the figures become extensions of the space, almost walls even–how the back of a t-shirt with a logo can become a partition of space or depth. There’s a small painting of a figure fading into the interior of the space, a merging or locating oneself between two things. Running with the eclipsing of color mentioned before, the moon has this strange ability of simultaneously appearing flat but volumetric depending on the lighting conditions. I often think of the mental image of a figure caught in headlights–a washing out or flattening of volume in space because of the intensity of lighting conditions, creating a silhouette. It feels very cinematic. The same for a figure backlit or in shadow. This, of course, has to do with color and I believe that the concerns of the paintings are based in color whereas the drawings concerns are more paired down. Secondly, as a kid I was not so much drawn to comics but to graphic novels, mostly for their storytelling abilities and how they convey space, point of view, and narrative arch. There’s something about the flatness of that graphic visual medium that I’m visually drawn to.

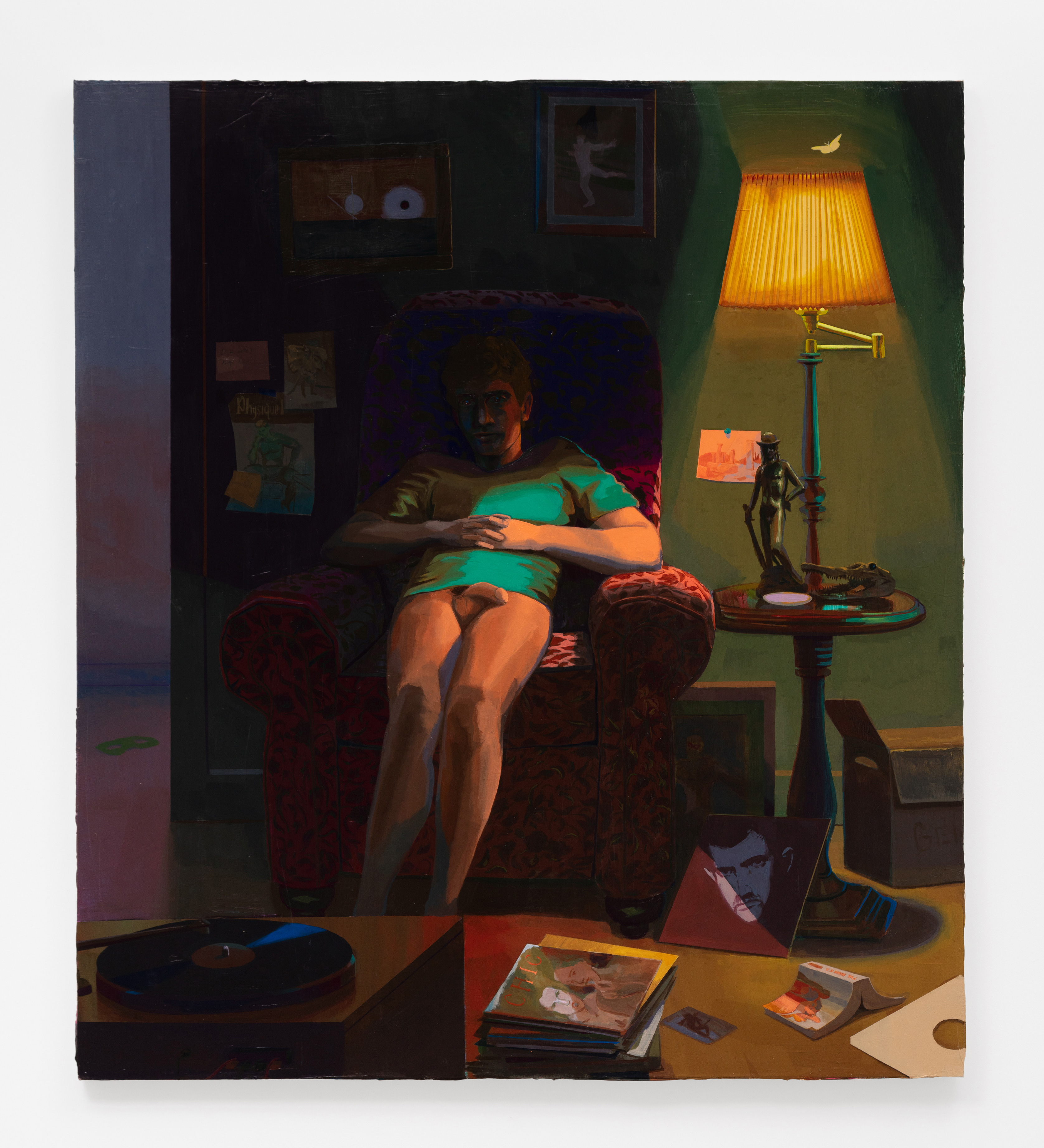

Robert Storr: Your full-to-overflowing answers to my first set of questions prompt all sorts of follow-ups. But before going down those rabbit holes let’s turn to other obvious characteristics of this set of paintings, which are more explicitly homosocial - and homoerotic - than the balance of the work you did while at Yale. There could be any number of reasons for that shift in emphasis but let’s content ourselves for now with pulling that thread and seeing where it leads. In which context my initial query about the nature of your painting process and your way of imagining things comes to the fore again. Are these encounters between men - or boys - staged? Or are they fantasized and then made real? Are these specific people - the boy sprawled in the armchair seems to be a drawing from life and a preparatory study for the painting which is still in progress - or is he a longed for “Adonis” made manifest? Does it matter which one they are, or is the image self sufficient as is?

Jacob Todd Broussard: I’d answer with a both-and response. Formally, these figures are part imagined, part real, pulled from various source materials. One key source is those mentioned drawings of Harry Bush. I came across one in an uploaded PDF online archive of Cruise Magazine (a late 70s publication that touts itself as “a guide to gay entertainment in the South”). The drawings are simple yet effective, with Bush being a master draftsman, and often depict youths in an erotic context but I noticed how some drawings also depicted them in a contemplative state, lost in thought or loneliness even. Some images were coded more than others, but I’d recreate the drawings through my own drawing or through posing myself and using photographs. There was a tamping down on the physical erotics of these bodies and more of an emphasis on that contemplative state, thinking of that as a space of desire.

The scenes themselves are all imagined but the specifics are then sourced with intention.

The use of Bush’s drawings links the painting to an embedded desire, some more obvious than others, and using a Jessian approach of appropriation and transformation. It’s nothing I’d imagine a viewer picking up on directly but it’s something I’m more than comfortable mentioning.

On the specifics of who this figure is–I’ve been working with the archetype of the Hermit for a couple years now, which was brought about by meditating on the works and life of visionary artist Forrest Bess.

Through many rabbit holes, I arrived at Jungian psychoanalysis and Jung’s approach towards thinking about the archetypal image. These are images and characters that present themselves again and again across history, myth, and cultures, containing their own specific resonances and meanings. The counter to the Hermit archetype is the Peur Aeternus - a child god who is eternally young, a figure of Peter Pan syndrome. If the Hermit is bardic, Apollonian and knowledgeable, then the Peur Aeternus is carefree, intolerable of restriction, and Dionysian. So there’s a clear connection between that and the spirit of Carnivale as a time where all the rules are reversed. But I was interested in the problem of the Peur Aeternus as a “failure to launch ” towards Individuation, of leading a provisional life due to fear of being caught in a situation from which one might not be able to escape. It stems from a fear of making the wrong decision, sacrificing freedom by saying yes to one thing and ultimately no to a thousand others. I wanted to think about the space of initiation–mythically, the act of a boy individuating by being brought into the wild, a transformation that requires sacrifice. Things that often initiate us are suffering and desire. And becoming initiated is being able to tolerate the sacrifice.

So this Puer Aeternus figure is a both-and: it’s both myself and Gene. I remember you mentioning from the shared photos of him that we have similar builds, there’s clearly a genetic connection. But there’s also the mythic. After what can only be described as a Spring of deep mourning, longing, and loneliness, I kept finding myself thinking about the past couple of years of my life. Can we truly know ourselves in the face of our own remembering and inevitable forgetting?

To your question asking if this is fantasy or reality: I've been thinking about this relationship between experience, memory, and the inherent gaps...

There’s a loneliness between all of those spaces. What remains? I think I went through my own personal initiative rites this Spring, learning how to be alone. Gene is interesting to think about in this context: he was married to a woman and had a child all before coming out later in his life. A latebloomer, he ultimately found community through the Mystic Krewe of Apollo which formed the year he turned 30; I’m 30 years old myself. These synchronicities forged the space to think about this Puer Aeternus character in a state of being between things, between a transformation. In the paintings, I wanted to think about the action of moving between the family home to the gay bar. Gene and myself are Cajun French, a culture of oddness and shame where one wears a mask often in a culture of masks. There’s the psychic space between the home and the gay bar. The figure who’s sitting in the armchair in a domestic setting is surrounded by things I consider objects of transformation. In another painting there’s a figure cleaning out what appears to be an old home and coming across a box of memorabilia, a photograph of a twirling figure. Then there are the scenes of a nightclub and a dj booth or a rave cave. Homosocially, the gay bar is a space of initiation, of ritual even. I equate it to going to church–we go out to remind ourselves of who we are and what we do.

Robert Storr: Who is your ideal audience for these paintings? People who in a sense already form part of the world these guys inhabit? Or people who live in adjacent worlds unaware of what is going on close by or underneath the surface of the “normal”? People, one would hope, could enter into your reality by means of your pictures and in the process come to terms with it and an enhanced understanding that no monolithic reality exists, there are always layered realities, traces of which show around the decal edges of dominant culture.

Jacob Todd Broussard: Audience has always been a struggle for me. I often feel a bit in the dark about this question and I try not to let my own conception of audience predetermine the things I do in the studio, however we can’t ever escape it. To your point, I’d hope that people would be drawn to the images as mysterious objects, ones that intrigue and spark longer looking than quick reads. That’s been a point with the paintings–to catch a viewer and to hold their eye for a longer time. The mention of there being no monolithic reality is foundational because it brings up perception: what I see is not the same as what someone else sees and that’s really interesting, good and bad. I could never fully know someone’s full range of experience, I’m often trying to make sense of my own which contains its own mysteries. The traces you speak of are of interest to me because they feel like subsets of genres, like music. They exist on the margins and surprise us when illuminated, showing us a range of invention and ways of becoming.

Robert Storr: Your imagery not only includes recently discovered pictures taken of your late cousin Gene dancing ecstatically in his extravagant Mardi Gras costumes – which like certain colorful insects are, as a rule, short lived and never seen again once their moment of glory has passed. But within your densely packed painting also appear unmistakable miniature renditions of classic paintings, most recognizably Gustave Courbet’s The Stone Breakers (1849) which is tacked to the wall of a darkroom irradiated with unnatural light (B2B Rave Cave ). So I would say that as much as anything Time is your thematic preoccupation. Youthful beauty as a fleeting phenomenon, beauty in any form as a fragile and inherently perishable thing – after all, that Courbet was destroyed in World War II as surely as the men in it are pulverizing rocks – and so on. Am I correct in assuming this? There is to that extent a measure of anticipated nostalgia for everything you depict – because you and the viewer are keenly alert to the fact that nothing lasts.

Jacob Todd Broussard: Yes your intuitions on time are correct and thank you for picking up on these breadcrumbs, specifically the Courbet painting and its fleeting life forever lost. While thinking about Gene–also somewhat lost to time–I kept returning to this question on the moral dimension of memory: what right do we have to forget? Where the archive ends, if one even exists, is where we consider how fantasy can be utilized to ask larger questions. Also, what does it mean to reflect on oneself, or one’s life through the life of someone else? There are clear parallels between myself and this person, but I am limited in access because of time so Gene becomes a frame for me to consider several things, but specifically time and its relational quality to love. I think of time moving in both directions. It’s a Janus and we’re always caught between it, we can never escape it. And to love is to lose something eventually. After what’s been a season of loss, I felt that I just couldn’t get around it while processing my grief. Obviously, a big, loaded term like love feels too amorphous to tackle all at once and I sort of hate even mentioning it but it does lead to interesting observations surrounding time and value. Why do we crave it when we will clearly experience its loss somewhere along the way? The show’s title, Afters is a play on temporality and its abbreviation for an afterparty. It alludes to something to come while also riffing off what remains after something has ended. Most certainly, it is memory. In a monastic sense, I willingly isolated myself this spring by participating in a six-month residency on a 30-acre property in South Louisiana. And through that isolation I began to reflect on memory, my own and some which I would like to hypothesize on for Gene. That particular painting (B2B Rave Cave) is a semi-invented memory, part my own, part Gene’s. I’ve built incredible community through nightlife across the Rust Belt, but specifically in Buffalo, NY where I was located for two and a half years. In my isolation, I used mixes of these friends as the soundtrack to my studio. The DJ is of course her own alchemist, with sampling, blending, and transforming a song being the alchemy. I wanted to make a painting of a DJ booth, one that blends my own memories of these past few years while imagining this as the space inhabited by Gene and his community. There are little hints and nodes to that era–the reel-to-reel or the back of a t-shirt having the Krewe of Apollo logo. But also there’s the depicted record in hand, a vinyl of the late EDM pioneer Patrick Cowley which was released just last year by Dark Entries Records. Of course, this record didn’t exist in 1977 but I like to think of painting as a space where all these things can come together to cast a spell. It can all become atemporal or existing out of place. Regarding the light in the painting, I think often of Bonnard and how he would paint light so specifically informed by his memory of a previous experience, as opposed to direct observation. He needed distance from observation in order to obtain a particular image and effect in the painting. So light then becomes a formal mediator of perception and loss. Which we could tease out and link it with time, I’d say.

There’s also this play on endurance–the endurance to continue dancing to the four-on-the-floor beat of house music as the never-ending party continues. But to endure also alludes to some sort of suffering, the endurance of memory, the pains of nostalgia and its trappings. There’s also the endurance of painting–a level of rigor and commitment which is its own dance. It should be mentioned that my studio shoes are the same shoes I wear to go out dancing.

Robert Storr: Among the affinities I think we share is a liking for the work of Jess whom I had the good luck to visit in his San Francisco studio shortly before he died. Jess grows in my esteem every time I see his work. He was so comfortable with aspects of his sensibility that generally scared off other artists in the postwar era: an open embrace of childhood fantasy, of old-fashioned graphic styles, of the Occult as an open field for dreaming and an utter lack of shame about it being a “soft” pseudo-scientific system of poetic correlations in an Atomic Age dedicated to provable “hard” facts of science. Are you drawn to the Occult in any way, do you feel a kinship with Jess?

Jacob Todd Broussard: I’m most certainly drawn to hermetic philosophical approaches towards art. It’s an unpopular position in a secular art world. But the Occult allows for new imaginings of existence and perception, one where coincidences aren’t just that: a coincidence. Mystical knowledge is initiatory knowledge that is revealed in experience. There’s a term I love coined by musicologist Phil Ford called “Diviner’s Time”: a particular feeling familiar to those who engage with magical or divinatory practices, namely a feeling that the randomness and chaos of the universe nevertheless contains a kind of music or rhythm. Not to mention, Cajun culture itself is steeped in pagan ritual even though it touts itself as deeply Catholic; it’s its own weird offshoot of Catholicism which embraces Caribbean, European, and Indigenous practices into its milieu. And ritual gives an experience a sense of causality, it marks time with significance, much like the celebration of Carnival.

Regarding Jess, I think of his personal aesthetic in kinship with the folk art I grew up looking at; I spent more time in strange spaces of self-taught artists and craftspeople than in art museums. There’s an insistence with Jess’ work that I find deeply admirable–here’s someone indulging in their formal and conceptual interests in a way that feels entirely unique for its time. This troop of queer American outliers–Jess, Forrest Bess, Paul Thek–who were looking beyond preexisting frameworks to reconsider their sense of self, made new outlines, and grappled with the human condition of loneliness. I want to circle back to this notion of Diviner’s Time–me coming across that photograph of a relative and choosing it for a painting, unbeknownst to my knowledge of who it was, is a deeply psychic experience. Then there’s the play on his name-Gene, genetics. Some would roll their eyes and say it’s all circumstantial, but isn’t that what artworks are made to reveal? That buzz or hum of random things interconnected in strange ways? One last thing: I visited Gene’s grave before heading out of town. He passed away 23 years ago on June 9th and this exhibition opens on June 8th. And of course, I’m just finding this out on the eve of my departure for Toronto. Afters feels like just the right title for the show.

In memory of Gene Kearney Domingue, 1947-2000

Robert Storr (b. 1949) is a painter, educator, critic, and curator. He earned his BA at Swarthmore College in 1972 and in 1978 his MFA in painting from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He has exhibited widely in the United States as well as internationally. His work is included in many public and private collections including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven; and the The Mead Art Museum, at Amherst College.

He was a curator then senior curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, from 1990 to 2002. From 2005 to 2007 he was visual arts director of the Venice Biennale, the first American invited to assume that position. He has taught and lectured extensively, including at Harvard, RISD, and Bard Center for Curatorial Studies. Between 2006–2017 he was the Dean of the School of Art at Yale University. He splits his time between New Haven and Brooklyn.