Navigating the Periphery

Maya Beaudry in conversation with Kate Brown

Maya Beaudry recently spoke with Kate Brown about systems, the periphery as a site of possibility, and the ever-evolving urban landscape.

Kate Brown: A longtime influence for you has been a 1970 book called A Pattern Language. What is it and how are you working with it in regards to this new body of work?

Maya Beaudry: I think of A Pattern Language as an artwork very much of its time. It came to me via family, so I have a very nostalgic and emotional bond to it. I think it’s a really interesting document and way to present information.

It was written as one of a series of books presented as “building manuals”, which map out different patterns in the built environment. It starts with large city structures and networks of rural and urban spaces, and scales down to tiny details in the house, each pattern is connected to other ones. The idea is that as you build your project, you start with whatever pattern you can affect change onto and work smaller. It’s all about interconnectivity and how patterns depend on each other, and that when they all work together, a space has a quality that is a “living” quality.

The way that I’ve found it inspiring in recent years is that, rather than taking it literally as a building manual, it’s a pretty useful way to structure an art practice, because it’s giving you these tools to make a thing that is alive; you consider the way your practice is linked to your studio building and your studio mates, and the way that building is linked to the city around it. And then you can go from your practice, which is an amorphous thing, down into the art objects that you make and the details of how they’re made and how they circulate in the world and are connected to other people.

Kate Brown: One of the takeaways from Pattern Language is this consideration of the margin or edge as a vital space, something that is true both in architecture and in communities. The most biodynamic area for foraging in a park is often the periphery because this is where nature and humans come into contact. The edge is a place you keep returning to. Could you explain that continuous interest?

Maya Beaudry: There’s a general law that runs through the Pattern Language universe, which is that your building is only really as strong as its connections or joinery.

I ended up in this world of domestic fabrics because I had an interest in architecture and buildings as bodies or characters in our lives.The place where my body connects to a building is on the couch, in my bed, or sitting on a carpet—usually places where there are fabrics. Upholstery is a mimicking of the body; it has a skin, it has a filling, and it has a structure like a skeleton. And when you feel relaxed or calm it is usually in these soft, supportive structures, and they’re there for you when your body is vulnerable or needs to be held by the building. And that’s a boundary between the body and the building.

I ended up in this world of domestic fabrics because I had an interest in architecture and buildings as bodies or characters in our lives.

Kate Brown: The works at Towards deal with this edge using textiles, but you look at the outside surface, where the building meets the rest of the landscape.

Maya Beaudry: There was a recurring pattern I was seeing in Vancouver: there will be a block of sweet old houses, sometimes they’re a little run down, or on less desirable streets to live, some of them over a hundred years old. First, the land assembly sign goes up, then the people move out. Then, the houses start to deteriorate rapidly. The windows get boarded up, and they start getting covered in graffiti. To me, this moment of seeing graffiti on a house is when you realize that a house’s life is over.

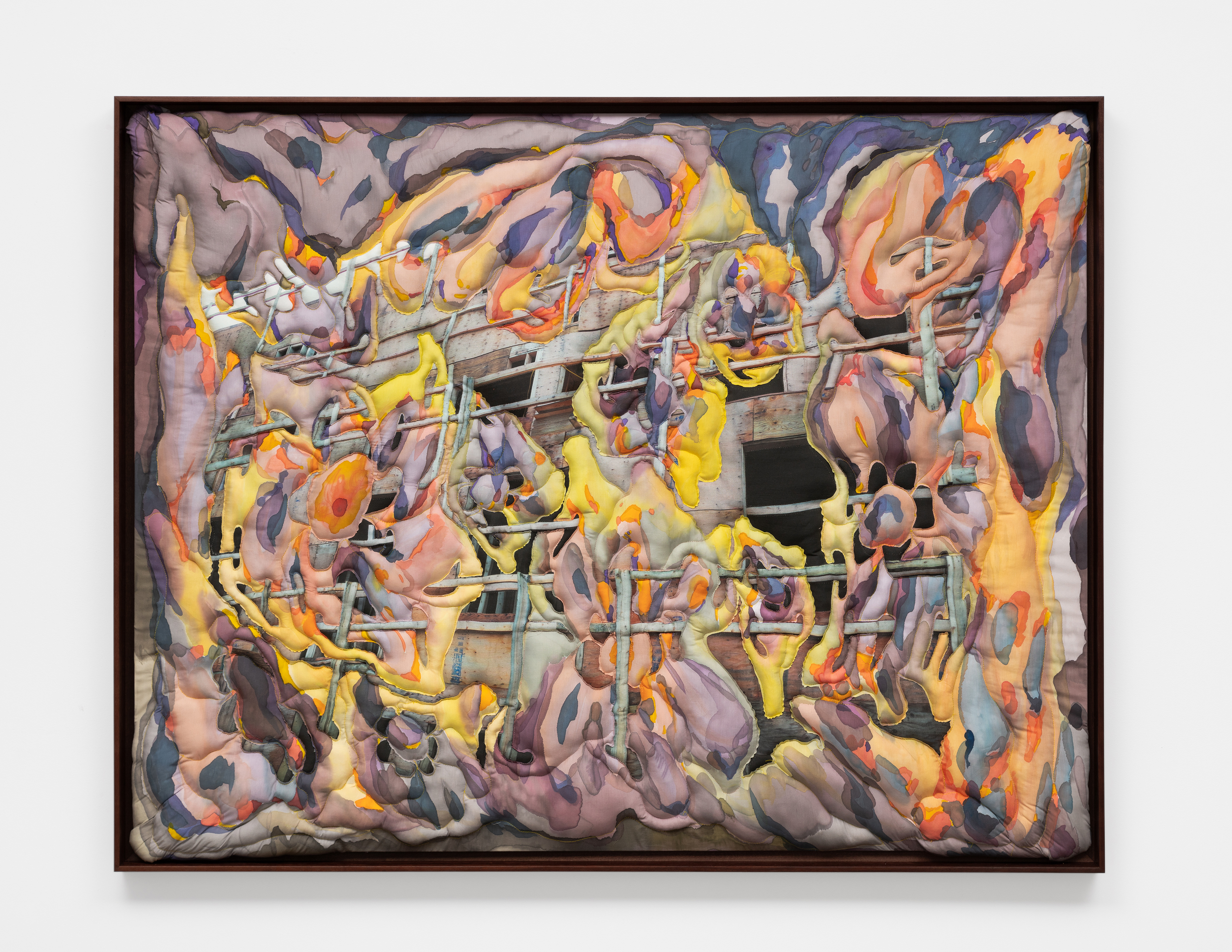

Digital pigment print on cotton, acrylic ink

39.5 x 51.5 x 2.25 in

Maya Beaudry: The photos in the piece called Lattice are from a building that I’ve been tracking for about a year. I wanted to go and take photos of these houses that had graffiti on them. The day that I finally got it together to go take the photos, they were gone— not a sign of them, totally flattened. It happened so fast. I started by taking pictures of the pit that was left and the signage that went up outside. And then I kept going back as the new building started to materialize.

There is also this moment that’s striking where the building goes up and it’s just the framed building—it’s two-by-fours and plywood. There’s something about that look that I was really drawn to; I think it was the repetition of this form all over the city. I was trying to do these compositions where a painted element weaves around an object that’s photographic. The lumber structures are formally really good for that, because they have all these holes and spaces for the painted object to circle through. There’s a moment with a building where there is no inside or outside when it’s being built. And then something happens; windows go on, or the plywood goes on and all of a sudden, there’s an interior space. It’s this imaginary structure before it has a defined inside and outside that was the zone I was working in.

Kate Brown: In those paintings, it both looks like it could be the beginnings of a shelter, but also the beginnings of a virus or something that’s bringing the structure down. There is this oscillation between two states. Even the way you described those buildings, they are in that instant both alive and dead. Is making art about this situation in your neighborhood and in your community a form of managing disillusionment? There is this broken promise of modernity.

Maya Beaudry: My instinct is to be devastated every time an old house gets torn down. I know that single family housing is not an efficient way to house people in the city anymore, but I don’t trust the people in charge. I try to be open to the fact that this is a period of intense change in Vancouver, but with the amount of people being displaced and being pushed out of the city or living on the street it feels like it is a very broken system. I wanted to document some of it as it’s happening.

Housing and real estate and gentrification in this part of the world are the legacies of colonialism and resource extraction. There’s a very dark history here and there are a lot of ghosts. I think there’s a project underway to clean up some of these haunted parts of town, but I think that having everything be new and shiny and losing that connection to the past is very scary.

Kate Brown: How do you build up the images? I think what’s unique to your practice is this time intensive layering you undertake, that has elliptical and cyclical processes to it.

Maya Beaudry: There are a few different ways. I’ve been doing these paintings with acrylic ink and water on really thin cotton. It’s similar to watercolor, but less controlled. Sometimes, I’ll make a painting and then I’ll have my collection of photo fabrics and a certain combination of painting and photo will resonate. And then sometimes I’ll make a painting with the intention of combining it with a specific photo. Then I layer the images up, and sew around certain things that I want to keep and then cut away the negative space and the layer underneath is revealed. This process is exciting to me because there’s a good balance of intention and surprise. You can direct it a little bit, but there are a lot of unknowns.

Digital pigment print on cotton, acrylic ink

46.5 x 47 x 2.25 in.

Maya Beaudry: The piece Skeleton was the first one that I made out of all the other pieces for Tree Museum. I had less of a clear idea of how to do this process when I made that one, so I figured out a lot of the technique while working on it. The goal was to get two layers of fabric to intertwine in a way that makes it hard to tell which layer is on top. This is also why the compositions are puffy, because it raises both layers to the same plane, and gives it this relief quality. The idea is that the photographic layer and the painted layer are different dimensions, and that they can be woven together to make a synthesis of these different modes of representation. I don’t know if I’m really there yet, but that’s the goal.

Kate Brown: In that particular work, there is still an element that is purely photographic. A ladder is visible on the side. It is real world subsumed by this created world. How do you move between abstraction and figuration? Many painters tend to identify with one category over the other, but in your work that boundary is completely dissolved. Is it something that you consciously work to do?

Digital pigment print on cotton, acrylic ink

46.5 x 47 x 2.25 in.

Maya Beaudry: A lot of people obviously are working on this—the balance of abstraction and figuration. I have a painting practice where a blob of color goes here, another color goes there. It’s an activity that I find pleasurable and fun to do when I’m feeling relaxed. But I find a lot of the time, it doesn’t quite feel like enough to me because it’s so outside of the world and references and subject matter. And I find that the photo fabric and the painted fabric butted up against each other looks closer to what my imagination feels like. My brain is full of photos that all bleed together and I like density in an artwork in general. When I was working with found fabrics, I kept trying to find patterns that had more density or complexity, and I realized that a photograph printed on fabric would have that quality, and would also bring in another spatial dimension.

My brain is full of photos that all bleed together and I like density in an artwork in general.

Kate Brown: Photographs also function differently on an emotional level. Paintings don’t quite have the puncturing quality a photograph can have, that punctum. I think especially when you’re making these images that are quite divine, almost like divine fractals, these photographic images give an opportunity to have the composition touch back down again. Another work in Tree Museum that feels sublime but also of the world, is this painting Childhood Home. Is it from your old house?

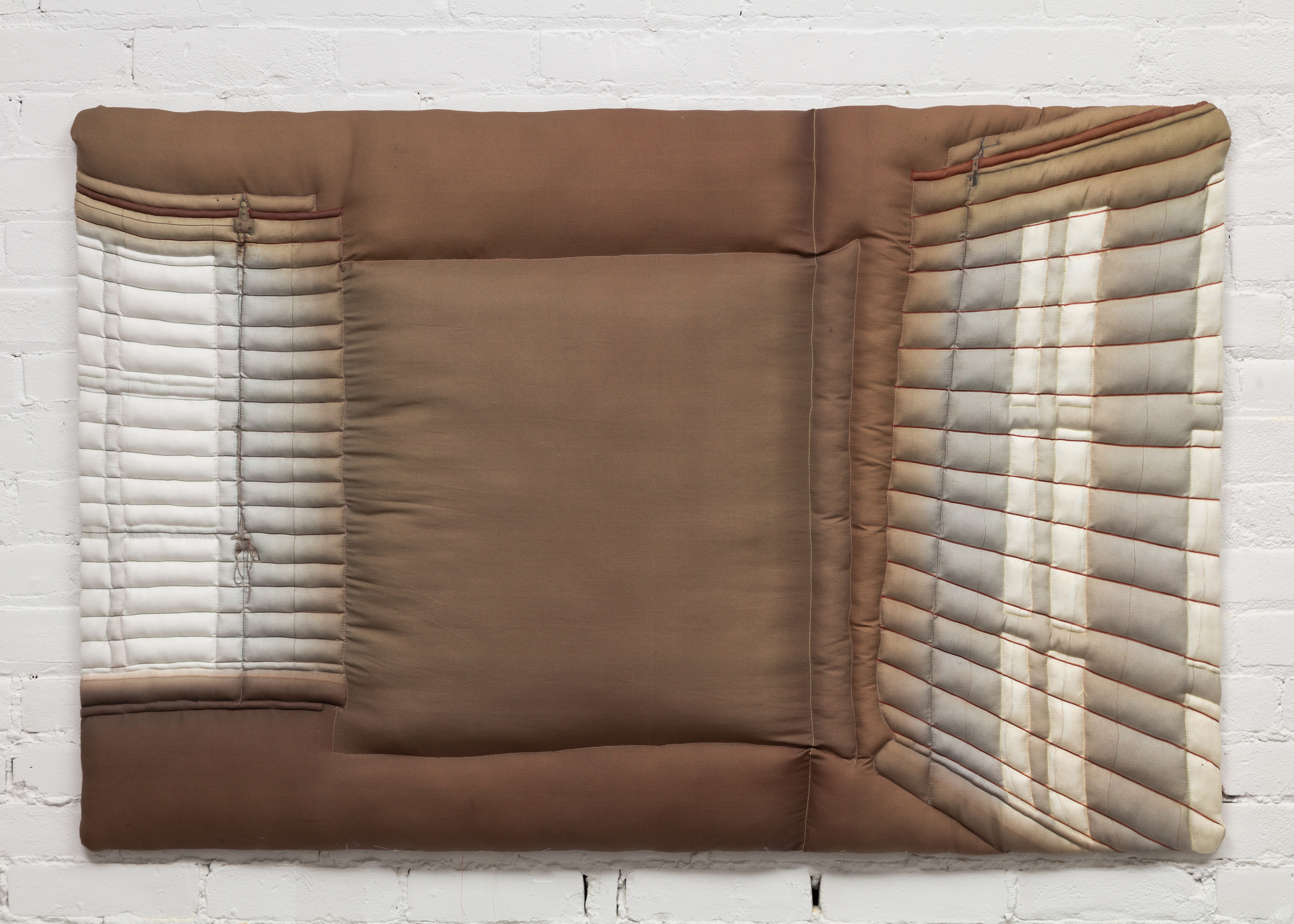

Digital pigment print on cotton

33 x 51 x 3 in.

Maya Beaudry: Yes. When my family moved out I took a bunch of photos when the house was empty, and was sitting on them for years. This unremarkable photograph of the corner of a room, just slightly distorted, is a bit more what my memory of space is like. When you think about a space you don’t have access to anymore, or when a building gets torn down and you can’t remember what was there before, sometimes the details you remember feel arbitrary. So I think that one was about a void. Maybe you don’t have access to your childhood home anymore, but it’s embedded in you. One part of this show that I was interested in was the psychic imprint of a space, and particularly buildings that aren’t there anymore. With spaces from childhood, they live in you forever, and you live in them forever. Because your brain develops around those spaces as it’s growing.

Maya Beaudry: This is where the Joni Mitchell song comes into it, too. I really stewed on that song as a little kid. I thought about it a lot, I could picture the Tree Museum, it was a real place to me, it had an architecture that sort of made sense, I could move around it in.

Kate Brown: That Joni Mitchell song is sweet, but it is dystopian. It’s a melancholic song wrapped in a happy melody. Maybe you could speak about melancholy, it hangs in a perfect suspension in some of your works, I find.

Maya Beaudry: It’s a very Vancouver state to me, because you’re just constantly being awed by the natural beauty here, and then shaken back into reality by the staggering inequality and dysfunction of the city.

To me, the idea of they cut down all the trees and put them in a tree museum is to take a living thing, contain it, and then charge money for access to it. There are so many structures and institutions you could apply that metaphor to. Specifically I was seeing it in the marketing for the new developments that were going up, particularly this moment when the houses have been torn down and the fencing goes up around it with the branding for the new development. A lot of the time they will use imagery from the neighbourhood, people on bikes, at cafes etc, to sell the neighbourhood back to itself, while pricing out the people who actually live there. A lot of this work is a very personal way for me to process my own position in all of this, physically and spiritually.

Making something that feels really personal and close without it being about yourself is a challenge. Trying to take my experience and my way of feeling in the world, and to take out personal details or not center my story in it has taken some time. My goal is to make something that feels bigger than my own experiences.

Kate Brown: How does time work for you in the studio?

Maya Beaudry: I have a sense of what I want my work to look like in 10 years, but I need 10 more years of learning to get there. I need to learn each element of a work deeply before I can move on to the next one or before I can scale it up. This is probably Pattern Language brain, because each building block has to have its own logic and energy in order for it to properly bind to the next element.

Trying to take my experience and my way of feeling in the world, and to take out personal details or not center my story in it has taken some time. My goal is to make something that feels bigger than my own experiences.

The idea is that the work would eventually take on the scale of a spatial world that would have elements from these different moments in the present along the way. So it could be archival and futuristic at the same time. In general, I’m a pretty collage-brained person, more so than I am a painter. You have to be patient with that, cause sometimes you have one element that’s interesting, and the thing that fits with it doesn’t come along for another couple years.

I’m superstitious about numbers and patterns and I think it makes a lot of sense in the studio. Because if I follow these imaginary rules that I’ve invented, every once in a while, things line up in unexpected ways, because I was following the same logic all the way. And then you can have two pieces that make sense in the same way that are made of totally different strategies and thinking.

Kate Brown: It‘s kind of like psychic time travel.

Maya Beaudry: It’s actually a pretty simple art practice. I’m trying to illustrate some specific phenomena that feel alive. If I can follow certain patterns that are alive, that is personally motivating in all aspects of my life. Because when you’re superstitious, certain imagery or numbers beckon to you and make you feel connected to the world in a very mysterious way; to me those are signs to keep going, to keep working. And it doesn’t always make sense to other people, but it’s a personal mythology that is vital for me to staying alive and inspired.

Kate Brown is a Senior Editor at Artnet News, co-host of the Art Angle podcast and founder of Ashley, Berlin.

All images of Maya Beaudry in her studio by NK Photo