Without representations, we don't exist

Maria Trabulo in conversation with Esmé Hogeveen

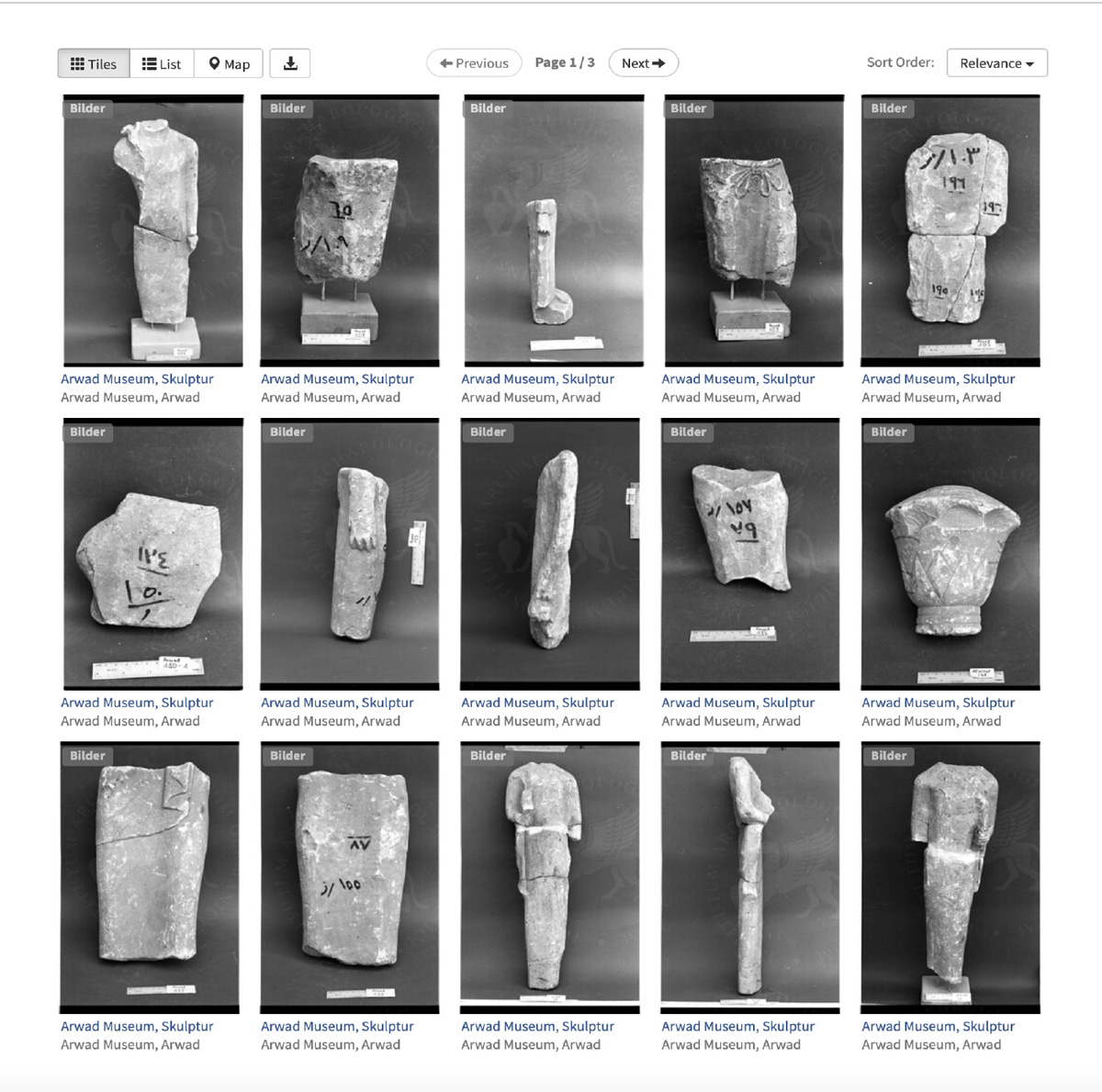

Esmé Hogeveen: What prompted you to work with digital archive images from Syria? And, on that topic, how did your collaborations with The Day After (Istanbul) and the Syrian Heritage Archive Project (Berlin) emerge?

Maria Trabulo: Wake Up the Statues is part of a larger body of work entitled “The Reinvention of Forgetting”, initiated in 2016, that departs from the role that the production, destruction, preservation and reproduction of images and cultural objects plays in our collective memory and shared history. In the course of this, I develop new artworks from the content of museum collections and archives that were damaged, hidden, or destroyed in result of a political act such as conflicts or civil uprisings.

In the context of this series, between 2016 and 2018 I visited the deposits of the Bode Museum in Berlin, in preparations for an exhibition at the Serralves Contemporary Art Museum in Porto. I was interested in a group of WWII surviving fragments in their collection, that told a story of conflict, separation, pain and healing, destruction and reconstruction throughout the 20th century up to our days. What was interesting about those fragments, was that they belonged to pieces that had been selected from the basements of the Berlin museums, and stored in bunkers so that they could survive the war. Thousands of other pieces were left behind, either because they were too complicated to transport, or because they were considered of less historical importance by those in charge of that task at the time.

I was fascinated by this decision of what is worth keeping and what is not, because it means to decide which history will remain and be told for posterity, and this defines the present time and the future through what gets to be remembered and what does not.

I was born long after WW2 ended, but the conflict is embedded in the collective memory of all generations born after it, including mine. In 2016-2017 a time when the 2008-2014 uprisings that spread the globe from East to West seemed to have called truce, and fascist and populist movements seemed to be favored in the West, the memory that these Berlin fragments carry made even more sense to be told.

During the summer of 2018 in Berlin, as I visited museum deposits filled with what was left of artworks destroyed, and of what had survived to the attacks of the city in the last weeks of World War Two, I scrolled through posts, videos, and images of the destruction of Palmyra among other sites in Syria on my social media feed. As I wandered the rooms filled with fragments of artworks that told past story of destruction, division, and reunification of Europe, I navigated online through the live destruction of cultural heritage, in a repetition of history. The effort in safeguarding artworks behind the walls of a bunker seemed like a poetic gesture of safeguarding the cultural story of a region, and this experience of war and destruction in the past and in the present, sparked my interest to know more about what efforts were being made in Syria to safeguard the uncountable historic sites and objects that could be found there before 2011 when the war started.

The past of destruction of cultural heritage in the Middle East, provides a history of abuse of that region by different powers. In fact, some of the objects destroyed in Berlin had come from there. The Syrian civil war and subsequent loss of cultural heritage, provides an impression, in real time, of the loss of history, but also of the use of the destruction and preservation of cultural heritage as a political and military strategy.

It allows one to observe how the manipulation of history can occur through the destruction of cultural heritage: by destroying what represents our opponent we are erasing them from history. Without representations, we don’t exist.

The case of Palmyra is an example of that power balance. Once the site was bombed (both by ISIS and by the Russian military) a handful of western companies “specialized” in 3D reproduction took the bombing as an opportunity to show off their skills. As I researched more on this topic I came across NGOs and cultural institutions involved in producing digital archives of the Syrian cultural heritage and decided to contact them.

Founded by Syrian historians and archaelogists in exile, Syrian Heritage Archive Project and the The Day After-Heritage Protection Initiative came to exist in response to the need to control the loss of their cultural identity in real time, by trying to gather any information on the objects or sites that had been destroyed or damaged, the ones that were still standing, document what was being taken freshly off the ground in undocumented excavations, and what was being smuggled out of Syria. They aim to gather old documentation and digitally document the current state on as many sites destroyed or damaged and artifacts lost in Syria during the civil war. Their action is possible through a network of Syrian archaeologists, historians, and museums both in site and in exile. The files are sent via WeTransfer or Whatsapp to email addresses and phone numbers in Europe, and stored on hard drives, from which they can one day be extracted to display these pieces in digital format. Their action of preventing the extinction of culture through documentation anticipates that in the future they will play an important role in the reconciliation of the country through culture once the war ends. The documentation they have is unfortunately insufficient to produce an exact reproduction of most of the artefacts, so within the scope of Wake Up the Statues, in collaboration with Syrian Heritage Archive Project and the The Day After-Heritage Protection Initiative that contribute with providing me access to their digital archives, I have experimented with ways to complement the “uninformed” artifacts in their archives, through the making of sculptures that tell the story of their disappearance, such as those exhibited in Toronto.

I understand that you sometimes draw upon oral histories and eye witness accounts to inform your understanding of specific objects rendered in archival images. Can you say more about what kinds of resources you consult and what information you’re seeking?

Yes, I often draw upon oral histories and eyewitness accounts to inform my work, particularly in the research phase, and not just in the case of archival images. Who I speak with varies according to the topic of research and the nature of the archive from which I am developing the artworks and my research. Whenever possible, I travel to the location and talk to the people behind the origin/founding of the archive and those in contact with the content/materials in the archive that I am interested in. What is crucial but not always possible, is to collect oral accounts, memories, and stories from people whose personal history intersects the archive. In the specific context of this series Wake Up the Statues I’ve had the privilege of having both experiences. Despite the digital format of its content and materials, the Syrian Heritage Archive Project has an office in Berlin that I’ve visited. There, the archive materialized in the form of a team formed by human beings moved by the invincible and touching force of gathering the memories and pieces of their fragmented material culture, supported by a group of local historians and researchers from the Islamic Museum - Berlin State Museums.

The advantage of visiting the actual sites of the archives relies in the possibility to interact with the people behind them and collect their stories. In the case of the Syrian Heritage Archive Project, meeting the team not only humanized the digital files, as the long conversations I had with the team in situ, allowed me to gain access to inform my research and better understand their process in collecting and organizing these materials. More recently, the collaboration has developed to collecting reports and accounts from the members of the teams that are not in Berlin, but in Syria documenting and photographing, sometimes in life-threatening conditions, with information (such as materials, size, color, memory of how the piece looked like from another angle) that can complement the images in the archive and inform their representation of the lost artifact.

What criteria do you consider while studying visual archives? I’m curious about your process for selecting images to transform into three-dimensional artworks.

In the context of Wake Up the Statues, the premise is to work from images that offer little or no chance of allowing for a subjective reproduction of the object: uninformed artifacts. This refers to pieces that were documented with just one photograph (offering only one viewing angle), or which files have low quality, or about which there is no more information to complement the image (such as the size of the object, location where it was found, materials, color, etc.). I chose to work with those images, because they document objects that only exist in that (uninformed and poorly documented) state of one single jpeg.

Without an intervention, a search for more documentation about them, and an attempt to reproduce them and tell their story of disappearance, they cease to exist.

How do you approach archives of war and war-torn sites with care and sensitivity? Do certain archival images ever feel beyond your scope as an artist to re-render or re-contextualize?

I don’t always approach archives of war-torn places, but I do always approach archives that are linked to a political event from which they were generated, or that conditions their visibility. The archive of poems by authors and artists sent as political prisoners to the Azores from mainland Portugal during the Estado Novo regime (1926-1974) or the living archive of memories and images on Tehran Contemporary Art Museum before and after the Iranian revolution as told by those who experienced it, are also examples of that.

I think that from the moment that they touch such sensitive and traumatic subjects such as war, revolutions, exile, censorship, among others, a careful and thoughtful approach is necessary. In all cases, I find that the best approach to these archives is to travel to the site and consult them in person, but most importantly to involve the people that have founded them, studied them, and whenever possible to include those to which the archives refer to. Certain topics, stories, and archival contents (images, documents, accounts, videos,…) sometimes feel beyond my scope as an artist for me to include them in work. For this reason, I try to also produce other materials such as publications, video-documentaries, and public debates, that allow to broaden the scope of communication and discussion, and to include the knowledge and specificity of those that helped and took part in the research process.

Archives carry individual stories that are connected to our collective memory and history, in that sense, it’s not a task to be dealt with alone. In the end, I don’t mean to extract an answer or to come up with a solution or impose my opinion, but I hope that the resulting works can create the possibility for the awareness on an event in our distant or recent past and the consequences it has had on the local and global history.

Can you describe the material process of making work for the Towards show?

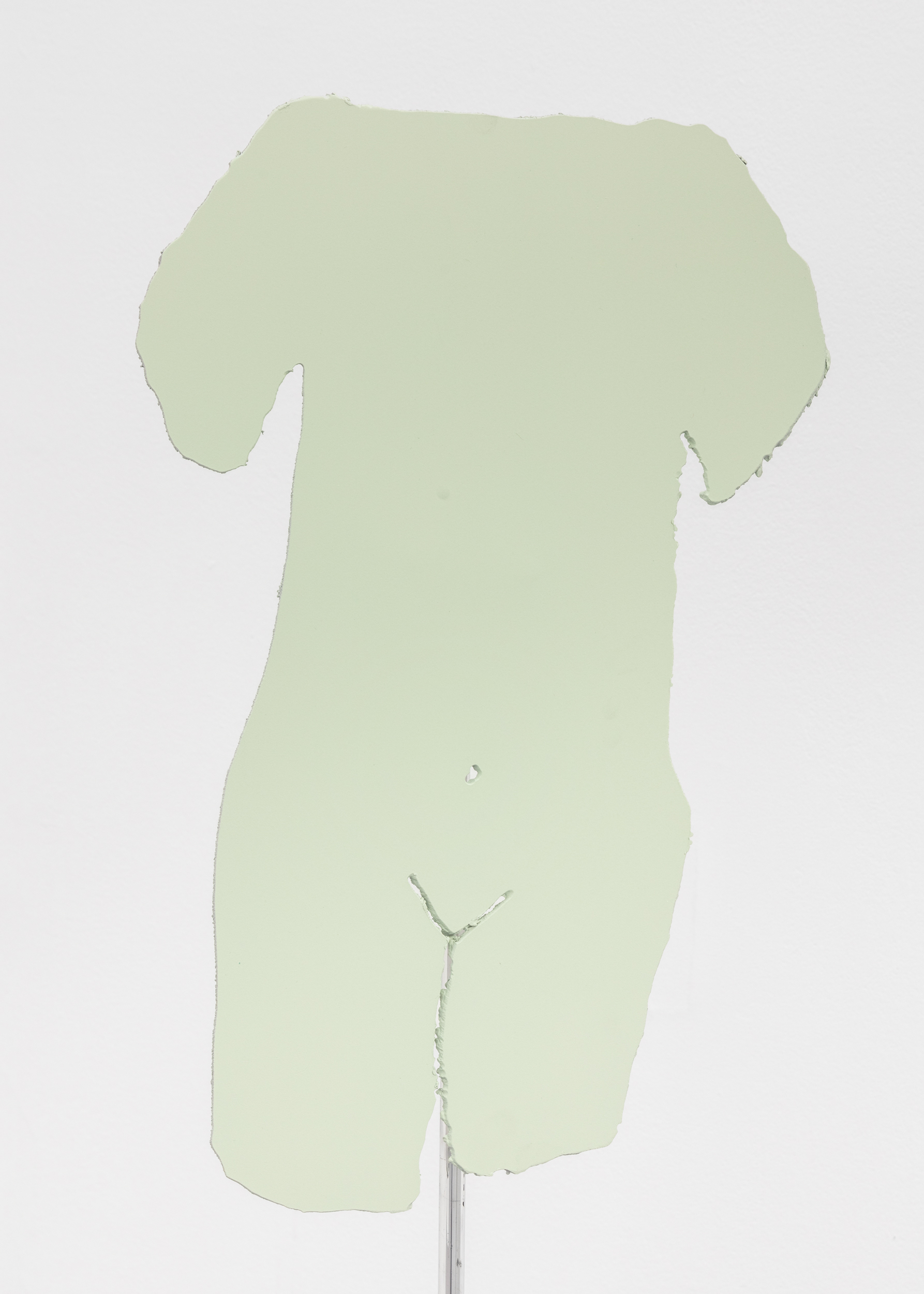

The series of sculptures in Wake Up the Statues was thought of as a collection of artifacts lost during the Syrian civil war. In that sense, each sculpture alludes to an image documenting a lost artifact that I took from the digital archives of the Syrian Heritage Archive Project and the The Day After-Heritage Protection Initiative. The resulting sculptures do not aim at representing objectively each lost piece, but at alluding the viewer to their disappearance. For that matter, only the outline of each artefact was taken from the images, and to preserve their origin in digital files from a digital archive, I decided for the sculptures to be flat. The series has a total of 100 sculptures in dimensions that vary from very small to large compositions of objects, each belonging to a group or division: Masks, Animals, Human Figures, Vases, Plates, etc. Wake Up the Statues was thought of as a collection that can be easily evacuated and transported in case of emergency, for that matter, the materials utilized, though resistant, are very light.

All pieces were produced with the support of Artworks, an art production organization located in the north of Portugal, at its workshops. The process consisted of projecting the selected images on aluminum metal sheets (2 to 3 mm thick) of several sizes and then I hand drew the outline of each object pictured. I then hand cut each drawing with a plasma cutter. The surface of each sculpture was finished in paint, polishing (mirror) or covered with a photographic print. These prints are from my archive of photographic scans (made with a portable book scanner) of surfaces of sculptures and objects (crates, boxes, pedestals) and materials (stone, metal, bubblewrap) found in the content of the archives and museum deposits that I visit.

A line from the exhibition text reads, “Prioritizing practicality over faithful reproduction, these modified artifacts are designed to be easily transported in the case of emergency.” Has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted how you anticipate your work moving—both physically and virtually—through the world?

The works in Wake Up the Statues were made in aluminum, a resistant but light metal, precisely so that they can be easily transported, furthermore, their size and two-dimensional aspect also intends to facilitate that. I see this as a poetic gesture of transporting the loss and the conflict and the stories embedded in the making of these works to the exhibition space. This is, to me, an important aspect in the works and in the exhibition, considering that the original objects that they allude to, could not be transported, and that dictated their destruction.

In the end, despite the pandemic, the works could be easily transported from Portugal to Canada, and the exhibition was set up in time for the opening. What was not predicted, but nevertheless suiting to the works, was that the city of Toronto declared a lockdown during the time predicted for the show to take place, thus, the gallery could not have visitors for most of the duration of the show. The exhibition thus became for online viewing only, which I thought was an interesting connection between the works that I did and the JPEGs they originated from: in the end, the memory or existence of both the lost artifacts and the works that I did, survived from having a digital form that travelled through the web, and perhaps the physical experience of the objects they referred to became of less importance.

I can’t anticipate my work moving physically or virtually through the world in cause or consequence or this crisis or future ones, because this is a concern that I had prior to how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the art world. I think we have always prioritized the experience of the object, but with this experience we’ve learned to contempt with a digital version of it, if it allows us to access some of it. In the end, the digital audience of Wake Up the Statues had to go through the same exercise as I did in the making of those objects: determine the size, material, and source.

Does the idea of homage factor into your work at all? If so, how does it relate to remembrance?

It is important to me that the works transmit the story of loss and conflict embedded in their making, and I hope that the idea of homage comes through the works as well. Particularly in the case of Wake Up the Statues besides highlighting the cyclical destruction and production of cultural objects, I intend to honor all people involved in gathering these digital archives, and the human effort (sometimes of lives lost) and time spent that goes into collecting what is left of their people’s cultural heritage, in the belief that this is what will bring them together, and repair the trauma, once the conflict is over.

Your work pushes back against notions of 1:1 representation of a “primary” or “source” object or image. Based on earlier conversations, I interpret some of your decisions around augmented scale to reflect practical concerns, i.e. keeping the works relatively small means they can be moved quickly in an emergency. Can you speak to your choices around palette though? There is an almost dreamy and quite contemporary quality to the pastel pinks, greens, blues, and white.

Most archival images that I used in the making of the didn’t provide an accurate information about the color of the documented artefact. They were either black and white, or lacked quality to discern the color palette objectively. For this reason, I created my own color scheme. The colors refer to extruded polystyrene foam, a material utilized as insolation for construction, but also commonly found inside deposits of museums or in the interior of crates designed to protect artworks during transport. Pastel blue, pink, green and white are the colors of this material in Europe, so they are a common sight whenever I visit the content of museum deposits. In conversation with the teams from the Syrian Heritage Archive Project and the The Day After-Heritage Protection Initiative I learned that this material was also being utilized by museums and archives in Syria to protect their content from the bombings. For this reason, the colors of materials utilized in the protection of artworks seems suiting for a collection of war-lost artifacts.

I understand that you often work with lo-fi digital images that offer a limited sense of the photographed object and its wider material or cultural contexts. I’m curious, then, if you think of the digital photograph or the depicted object as a primary source? – Or if the idea of a primary source is even relevant to your practice?

The source of the works are the images from the NGOs. They do a formidable work in tracking any information possible about the object, such as the place where it was found, to when the photograph was taken, by whom, and whenever possible, to return to the place and gather more information about it and document the object in better conditions. For Wake Up the Statues I have worked with images of objects that have disappeared or have been destroyed, and of which there is little visual documentation. Nevertheless, there is information about how, when and where the object was found and photographed, so there is a geographic and cultural context to these objects. However, they lack a detailed and precise visual information about them (exact color, dimensions, material) or they only provide one perspective of the object, which is also what I try to highlight in the sculptures I made for Wake Up the Statues. The source becomes what is visually left from the artefacts: a bad resolution photo and the oral memory of an object that existed.

In being lucky enough to see the work in person back in January, I was struck by some of the universal themes and images—outlines that suggest columns, female figures, faces, vases, and vessels recall ideas of capital-H History. The form of a column, for instance, has in many ways become synonymous with the past, archaeology, mathematical order, architectural prestige, social and economic order, etc. In what ways do you see your work as being about history or memory more broadly?

These outlines of columns, human figures, masks, and vases are shapes from specific and unique objects whose creation, existence and disappearance is connected to Syria. Nevertheless, together, they allude to a collective understanding of ancient history represented by artifacts, highlighting our shared collective memory and history originated in that region. One of the intentions in representing the lost artefacts with their outline, was also to allow for the viewers to project their own memories of representations of history and the past on them.

Wake Up the Statues is inseparable from memory and history, its origin lies in individual and collective fragments of both that I collected. Departing from the archival images of cultural heritage destroyed in Syria, the series explores the role of passing of memory through time that we impose to objects, as an extension of ourselves beyond our death, and how the destruction or loss of these representations dictates the oblivion or erasure of an event, someone, or a people from history, and the alteration or manipulation or historical narratives. To raise and destroy appears natural, and I’m reminded of the statues that have been toppled over and over across history, however, nowadays we seem to fear that destruction, and have come up with multiple mechanisms, to keep the objects that remember us: photographs, plaster casts, 3D scans, so that in case they’re destroyed, we can remake them. In conclusion, Wake Up the Statues observes the destruction of cultural heritage as a military strategy, and highlights the human effort to contain the loss in real time of a collective memory and the political importance of such, act and explores the importance of keeping all things in reference to all times.

Wake Up the Statues is inseparable from memory and history, its origin lies in individual and collective fragments of both that I collected.

The arrangement of several works in the far corner of the gallery (The Excavation Site) suggests a kind of graveyard atmosphere or a cluster of tombstones. Seeing this sombre grouping, albeit slightly offset by the colourful pastel tones, I was reminded of the absence of carnage or explicit references to human suffering or mourning. Do you think of your work as directly engaging death or its representation?

The title and idea for group of works The Excavation Site comes from a group of images that I was sent by The Day After-Heritage Protection Initiative NGO, documenting the illegal or undocumented archaeological excavations that became frequent during the Syrian conflict. Left with no other sources of income, civilians were left with no other option but to dig the ground under their feet for objects to sell. Artifacts became a form of trade for means to survive.

In one of my conversations with Amr Al-Azm - founder of The Day After-Heritage Protection Initiative - about the action of his NGO in preventing these excavations, he mentioned that “most of the looting that has happened in Syria, is what I would refer to as subsistence looting or opportunistic. Every Syrian, almost literally, lives either on top of an archaeological site, right next door to one, or within a stone’s throw of an archaeological site, to the point that there are urban legends or stories about someone who knows someone, who once was digging the garden and found a pot of gold. So as people ran out of options to provide support for their families amidst a war, they turned to this. By empowering local populations and making them responsible for their own cultural heritage and history, involving them in the protection process as site monitors or protectors, sandbagging, or documenting, we can guarantee their subsistence as we prevent looting.” The Excavation Site alludes to this event of digging the soil not for vegetables but for objects. In this process, thousands of artifacts go undocumented, not that they need to be documented, in my opinion, but their trade as a form of subsistence and thus as a form of life, seemed to me important to be told.

I don’t see my work explicitly engaging with questions of death or its representation, at least not in what concerns a war, if anything, I see it as dealing with representation through objects (works of art, artifacts) that compose our cultural heritage, as a form of extending our existence in time beyond the decadence of our human bodies.

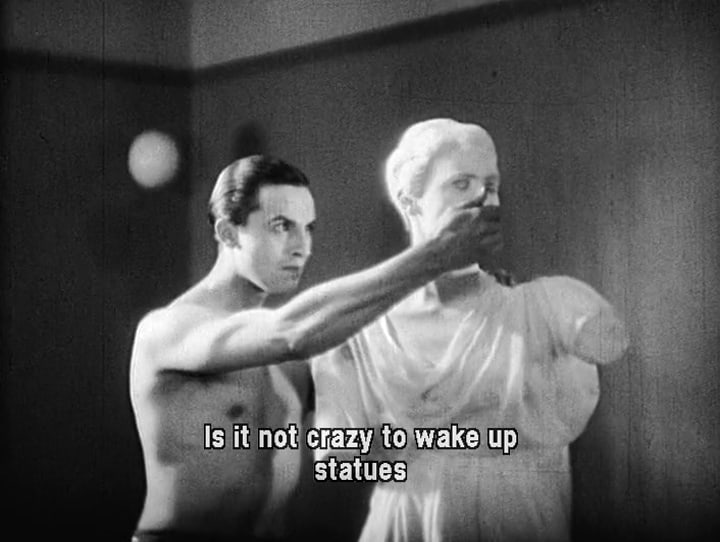

The inspiring efforts of Syrian Heritage Archive Project and the The Day After-Heritage Protection Initiative in collecting digital versions of their heritage, point precisely to the role that we cast in objects to represent us for posterity: humans become objects and objects become humans. For this matter, the title of the series comes from a scene in Jean Cocteau’s surrealist film Blood of a Poet (1930), in which the poet wakes up an Ancient Greek statue, then destroys it, and from the dust of destroying that statue he turns into a statue sitting at a square, that is again destroyed during a children’s fight.

Wake Up the Statues is part of a larger body of work that you’ve been developing over the last few years. What’s next in this series?

Wake Up the Statues is part of a larger body of work entitled “The Reinvention of Forgetting”. “The Reinvention of Forgetting”, departs from the impossibility to forget given the number of resources that we have created to remember and be remembered to explore the persistence of memory through cultural heritage (works of art/artifacts). This artistic investigation proposes to analyze the premeditated destruction of cultural objects during conflicts, uprisings and other political events, in order to explore the limits of survival of history through the use of the tools of (re)production and sharing of images that technology introduces, challenging oblivion.

At a time when remembering seems to be the norm and forgetting the exception, this artistic research The Reinvention of Forgetting explores our dependence on archives that extends to everyday life, museums, archeology and preservation practices, questioning whether memory loss is not necessary for historical progression: right to be forgotten. In a methodology that crosses art, history and technology, this research analyzes the potential for contemporary works of art to preserve, historicize and enhance memory, and the possibility of the contemporary artist to participate in the restitution of cultural heritage lost during conflicts.

The next step for Wake Up the Statues is to continue my collaboration with the mentioned NGOs, working on undocumented objects that went missing, collecting the oral memories that historians, archaeologists, and civilians have of them, constructing an archive of objects without images, but more importantly, an archive of human effort in rescuing their cultural identity while it is destroyed in real time. Upcoming in this series is also a new research in a museum archive in Paris as a guest artist at the Cité Internationale des Arts de Paris for an upcoming show, and furthermore I am also preparing a new research at the archive of the NS-Dokumentationszentrum München for an upcoming artist residency and solo exhibition in Munich.