The Excesses and Materials of the Everyday

Jenny Gagalka in Conversation with Clara Puton

Clara Puton: Jenny, you spoke of your preference for drawing, telling me how you feel painting is about building something up, whereas drawing is about tearing things down. It makes me think of your duffle bag. It has the possibility to be stuffed, fulfilling its ultimate form and the material limit that comes with it, and how you prefer to and sketch it when it’s empty, creating endless possibilities of wrinkles, lumps, and shadows that play with its malleability. Do you feel a correlation there?

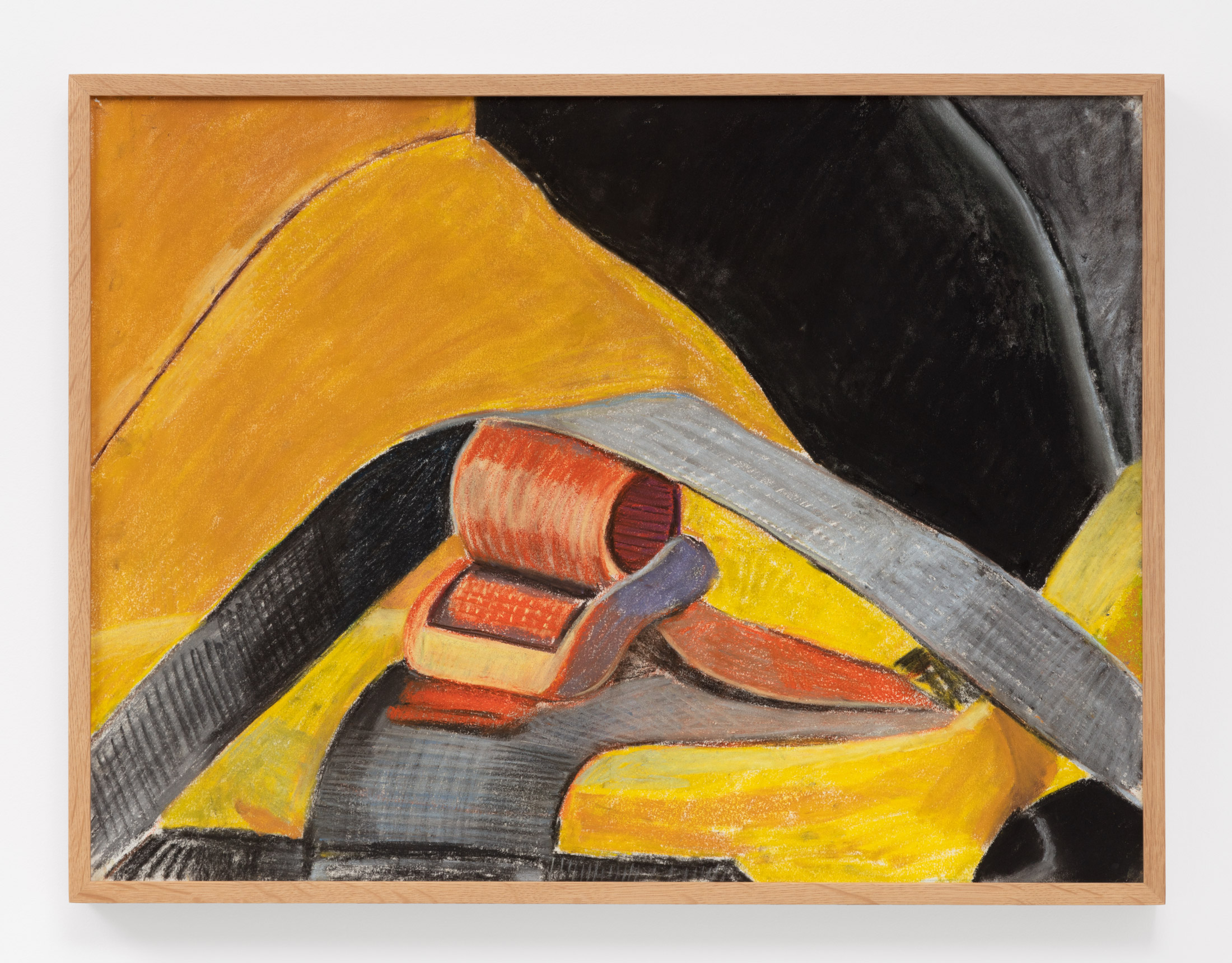

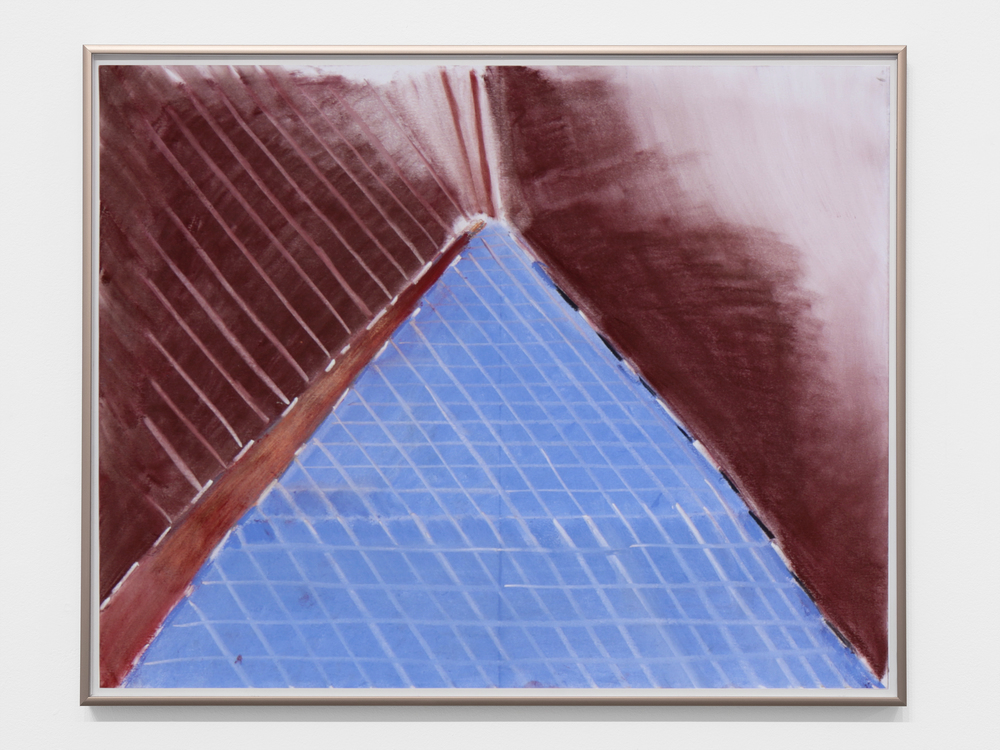

Jenny Gagalka: Definitely. My practice in the past two years has been focused on drawing and painting from direct observation of a couple mass produced items staged in the studio in countless configurations. Right now, I’m working on a series of paintings on canvas where I am looking at boxes of Pop Secret popcorn and recording these stacked objects which are at times opened and at other times closed. There’s something very uncomfortable about the ability to cover up with paint and by that erasing history.

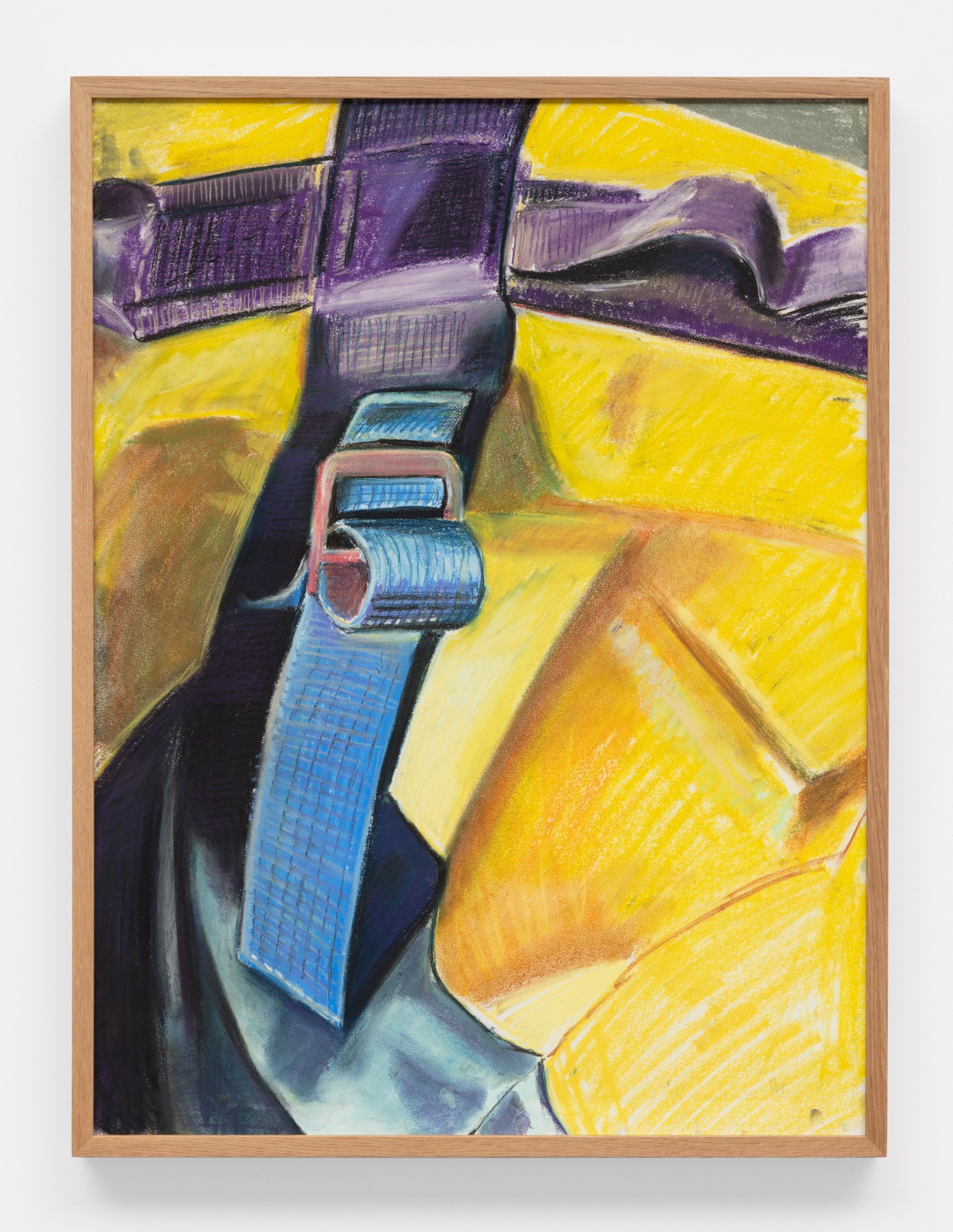

JG: Unlike the bag, the box remains unbothered regardless if it is full or empty. I find it interesting how the last series of the lumpy, malleable bag were approached via drawing with chalk pastels, while the rigid, flat popcorn box is approached with the fluidity of paint. So if there is a correlation of the subject to the physical materials used in making the work, it is a negative one. Like climbing a mountain (higher) gets colder (lower). I think this makes tension in the work, a feeling I think we are all too familiar with!

But of course there are many more variables at play. In the end, both of the subjects of the bag and the box remain recognizable yet removed from their functions and provide compositions that speak to divisions or partitions such as windows, fences, freeways

JG: There is always a disorientation of perspective or clash of various perspectives, such as the deep space of the interior of the box against the flatness of the exterior, and an aerial viewpoint in the drawings of the bag that messes with the picture plane.

Pastel on paper

18.75 x 24.75 in.

CP: I love your compositional description of the bag and the box, zooming in to find windows, fences, and freeways within their recognizable forms. It dovetails with their statuses as mass-produced objects – their forms becoming a vehicle to think about places of manufacture and the distances mass-produced objects travel to reach, for example, the grocery store and ultimately your studio. Could you speak to your attraction to working with mass-produced items? Your impulse to study, record, and distort them – whether they be a responsive object, like the bag, or an ambivalent one like the box.

JG: I have a friend who lives in Fairbanks, Alaska named Rachel Mulvihill who is a fantastic artist. She recently said how she loves that you don’t have to travel far to make a good painting. She does so by painting seemingly mundane views in her home or in the landscape immediately outside her door. Her works actually transport the viewer and herself much farther than her yard and speak to the complexities of a homeland. That attitude towards painting resonates with me.

I’m still trying to understand why the subjects are consistently these types of synthetic everyday items. It’s the point of departure, speaking of travel.

Maybe I am attracted to working with mass-produced items because I am so repulsed and seduced by them.

Pastel on paper.

24.75 x 18.75 in

JG: Maybe it is because somehow they go overlooked despite their design of flashy colors and vulgarity. The exhilarating world depicted on the exterior of a box of Pop Secret, for example, doesn’t correspond to the banal stuff that is happening on the inside of the box.

Everything in our environment, be it natural or synthetic and the self included, points to the conditions that shaped it. For me, observation is a practice of being present and slowing down and very much a mirror of one’s hidden mind. These works in progress over the past month are starting to look like confessional booths of sorts - a doubling of opening spaces in an ultramarine blue that had been restricted to the clothing of Christ or the Virgin Mary in Renaissance paintings like in Sassoferrato’s, The Virgin in Prayer.

CP: That’s a wonderful observation. Ultramarine blue – once a highly expensive pigment as well as one linked and restricted to divine representation – can now be selected on a digital palette, mass-printed, and applied to something like a box that contains the transformation of kernels to popped corn. Do you think in some ways you are pursuing the false idols of consumerism?

JG: I would say I’m not too engaged in that when making the work, but it’s definitely a conversation that comes up. . The fact that these subjects are crass commercial items are not exactly random but the procedure of starting a piece is contingent on an urgent impulse instead of Jenny thinking of an idea. The subjects of observation do have characteristics in common however, like that they feature folds and are vehicles for transportation and cloaks for concealment. Lee Lozano’s hammers, wrenches, and screws aren’t so much about those objects. They are paintings of tools for sure, but open up to something more disturbing and erotic in the way they are screwing and hammering again and again. The excesses and materials of the everyday.

CP: Your practice is enriched by close observation of what’s in front of you, engaging with repetition, in time-passing, in developing an intimacy with your chosen object. Could you speak more to what it feels like to have a singular object multiply across your work?

JG: In repetition, you can see difference. It works in relation and there is a power in numbers. Working in series came about pragmatically - it allows for more time and you don’t have to “figure it all out” on just one page or surface. But it has morphed as the matrix to the work.

I like that with seriality, the notion of a masterpiece is gone.

But these paintings and drawings aren’t copies of each other nor are they copies of the source object. There is close cropping, and drastic shifts in color (and although I try to be as objective as possible in rendering the forms and shadows, I think I end up exaggerating them). Through repetition and pattern it becomes highly charged and with a skewed sense of gravity suggesting an uneven ground, or compared to one another, many different grounds and moving perspectives. An imaginary ground, like language. A made up system with real implications.

Pastel on paper.

18.75 x 24.75

JG: Several years ago, I was in Las Vegas with my friend Beaux Mendes who works in plein air. I was drawing outside the Luxor hotel and no sooner had I put down a simple isosceles triangle on a blank page did a passerby stop in their tracks, 3 foot tall plastic margarita tower in hand, and sincerely comment “wow you’re so good!” while comparing the triangle to the building. [image here and here] Of course seeing something so analog in that environment would be so arresting. These bag and box works are performative too, in their abundance.

CP: I enjoy the clarity on how your serial paintings and drawings aren’t copies of the original nor of each other. While they might resist the classical definition of simulacra, I see a connection with Jean Baudrillard’s postmodern phase of the term that follows the proliferation of mass-production. In the postmodern phase, an image’s representation arrives at a point where it advances and determines the real source, eliminating the notion of an original in favor of a simulation. In the works we’ve discussed, there is a simulation of the object in front of you that is facilitated by this stimulation of gravity, cropping, color and shadow, perspective, and a lack of linear perspective. A loss of stable ground that opens up to representational freedom.

JG: That feels so right. There are so many things to negotiate when you look at something for such an extended amount of time and also while attempting to translate it into an image. Perceiving my own invisible construct, a mirror to the self while also engaging with this contemporary moment.

Those moments of instability slow down time engaging with the most stable medium of painting.

Jenny Gagalka (b. 1984 Vancouver) lives in Los Angeles. She received an MFA in Painting & Drawing from UCLA in 2018. She has attended residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Ox-Bow in Michigan, and The Mountain School of Art in Los Angeles. Previous solo exhibitions include Good Weather Gallery (Little Rock Arkansas), and ltd. (Los Angeles) with former drawing collaborative En Plein Error and group exhibitions at Human Resources (Los Angeles), and Páramo (Guadalajara), among others.

Clara Puton’s interests broadly traverse diverse approaches to historical and contemporary material culture and the intersections of art, craft, fashion, and design. She graduated with a MA in Design History, Material Culture, and Decorative Arts from Bard Graduate Center (New York, NY; Bard College) and also holds a BA in Art History from McGill University. Puton currently works as Development Officer at the Gardiner Museum. Previous positions include Gallery Manager at Patel Brown; Gallery Assistant at Franz Kaka; and Curatorial and Collections Management Intern in Costume and Textiles at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).