Argenteuil

On Two Recent Paintings by Tristan Unrau

An image must be transformed by contact with other images as is a colour by contact with other colours. A blue is not the same blue beside a green, a yellow, a red. No art without transformation.

— Robert Bresson, trans. Jonathan Griffin

1.

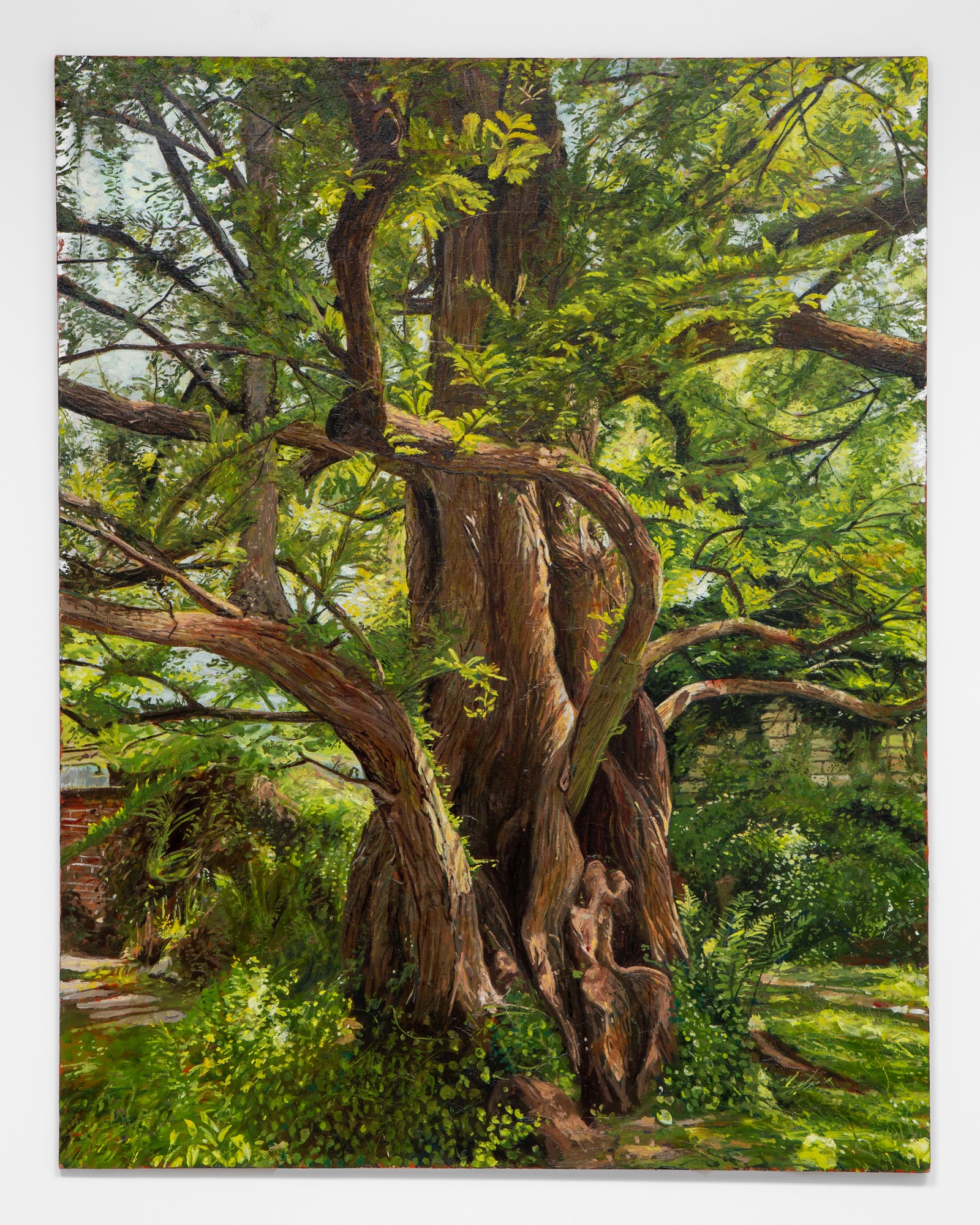

Look closely at Tristan Unrau’s oil painting on linen Metasequoia (2021): his brushwork blurs so that the needles of the tree have an impressionistic feel. From a distance, though, they have an almost photorealist illusion of depth and detail. Depending on how close you are to the canvas, the image changes focus. In this way, the painting has a tension between two kinds of opticality. Now, consider Floor (2021), the much smaller watercolour on linen next to Metasequoia. Rectangles of cherry red and moss green are laid out in patterns overtop a cream-coloured background. Its title provides a referent, suggesting that the pattern on the canvas is tile flooring, perhaps linoleum, instead of what otherwise might be taken for an abstraction. The two canvases unexpectedly complement each other, an asymmetrical diptych. Both provide us with ways of thinking about looking, how we process visual information differently depending on context.

2.

On 13 May, 2021, I returned from my daily run in the nearby Jardin des Plantes to the news that my wife had secured us an appointment for our first dose of an mNRA vaccine against Covid-19. At the time, in France where we live, vaccine supply was limited, and getting a rendez-vous for people under fifty was not easy. The next morning, we found ourselves in a taxi heading from the center of Paris toward a hospital in Argenteuil, an hour’s drive north-west of the city. The name resounded in my ears. As we crossed the bridges of the Seine, I had a difficult time imagining the post-industrial scene unfolding before me had ever been the subject of impressionist painting. It was grey and depressing. The cab driver took an extra ten minutes to find the entrance to the massive multi-block hospital compound. We exited the cab. On the sidewalk, a group of unmasked teenagers wore drab-coloured djellabas overtop sportswear.

It started raining. I thought of other images.

A woman wears a brown straw hat with a white ribbon wrapped around it. She has placed flowers in the lap of her blue dress. She glances directly toward us. Sitting beside her, a man looks intently at her. He has a moustache and wears a white-and-red sailor’s jersey, the sleeves rolled. He holds a collapsed white parasol in his hand. Behind them is the Seine, its docked boats, the shore across lined with buildings. Éduoard Manet’s 1874 Argenteuil is not a scene of nature, though the clothing its figures wear indicates that they are, at least, in leisure. In The Painting of Modern Life, T. J. Clark argues that places like Argenteuil attracted painters, because they were evidence of a new kind of modern landscape, neither nature nor city exactly, where the petite bourgeoisie could afford to spend their weekends. For that canvas, one of four Manet completed in the summer of 1874, he had asked Claude Monet and his wife Camille, who lived in Argenteuil at the time, to sit for the painting.

But apparently, they could not hold the pose. It may not matter, though. As Manet’s title suggests, the subject of the painting is not the figures anyway, rather the place in which they find themselves. They are instead examples of a type who frequent the shores of the Seine in the Parisian outskirts, its jarring mixture of industry and idyl.

As we left the vaccination center, we both wept. The strict lockdown in Paris had been difficult, and without a safe place to quarantine, we had been unable to travel home to Vancouver for over a year and a half. As soon as we were vaccinated, I sent messages to loved ones. I also posted an image to Instagram. It was of a tree: a metasequoia in a hidden corner of the Jardin des Plantes. Instead of a selfie or a detail of my bandaged arm, this particular tree seemed to represent the hope I felt at that moment. I wrote a note about receiving my first dose of a vaccine in Argenteuil, former site of impressionism. That image of the tree, I wrote, reminded me of a particular grove of balding cypress trees in Vancouver’s VanDusen Gardens, a garden in which I have some of my first memories of childhood, where I could imagine now being able to visit again. A bit woozy from the needle, we bought bottles of water and called a taxi and waited on the wide avenue, shouts of Arabic from the shopkeepers. An hour later, we re-entered Paris via Avenue de la Grande Armée. The Arc de Triomphe loomed ahead of us.

3.

Unrau saw my snapshot of the tree, saved it, and then (without asking me) made an oil painting of it. “I was struck by your photograph of a metasequoia,” he wrote to me at the end of August. “It could have been you connecting it to the cypresses at VanDusen, which I also love,” he continued, “or maybe it was connected to your use of that image as a way to mark the receiving of a vaccine, a nice bit of symbolism, or perhaps it was your mentioning of having received the vaccine in a part of the world which was at one point important to painting.” In this way, the photograph used to mark my first round of vaccination became the subject of one of his paintings, transposed from its original context to one that comments on, however obliquely, a particular tributary in the history of European painting. Metasequoia is thus loaded with this meaning and yet also exists without it.

This method of selecting a subject is not unusual for Unrau. He often chooses images from things he sees or reads; his work thus forms a sort of journal of referents. In this case, this image developed out of the way my picture led him through a thought process connected to the history of painting. This transforms the image, taking it from its original source and giving it a new context. I am reminded, to some degree, of Jeff Wall’s three works inspired from literary sources, what Wall has called his “Accidents of Reading”—images that appear to the artist while reading a book, which he then stages as a photographic image. What Unrau does here has something of the same logic: his subject matter is taken from another source and transposed into a painting. At least, that seems to be the case for the painting of the metasequoia; I suspect the case is similar with Floor. Yet, in the case of Unrau’s paintings, the original referents become unmoored. The source and content of my image, for instance, is reduced to its literal subject, a tree.

For Unrau, painting is a form of thinking. I suspect that by this he means both the process of making a painting and the visual composition itself, the end product of the act of applying brush to canvas.

He has been exploring his thoughts on his métier in a Google doc titled “Painting Notes.” The document is a collection of images, quotations, and jottings, similar in some respects to Robert Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematographer, the book in which the French director kept notes while making films. In “Painting Notes,” Unrau states that painting is a form of embodied thought: “Psychologists no longer think of the mind as going through a sequence of conscious ideas, one at a time,” he writes. “They suspect a great deal happens at once.”

An idea that has been activated does not merely evoke one other idea. It activates many ideas, which in turn activate others.” The same is true of looking at one of his paintings. Each one comes from a considered and methodological study, and yet they are presented simply as images, with a sort of sincere directness. They are bursts of thought; they are studies in how we look at things. But what I like about them is, they are not forced. His paintings don’t confront the viewer in an overly serious tone. As viewers, we are presented with the pleasure of the work, the brushwork, the colours, the subject-matter. The paintings can be playful, pleasant to look at, even sometimes funny.

4.

What then about Floor? Its patterns float. I’m taken by the way a simple word changes how we look at it. Once we read the title, the painting is transformed from a potentially abstract study into a representation of something in the world. Again, it becomes an unmoored referent, with a context that remains unknown (at least to me—maybe a friend’s kitchen floor, maybe his own?). Its word tethers us, but to what exactly we don’t know. Its meaning shifts based on whether or not we read the title.

So, this might be how these paintings work independently of each other, but what happens when Floor is placed next to Metasequoia? The stylistic difference between the two paintings is remarkable. Yet, that shift—the sort of ludic diptych that these pictures form—is, in many ways, Unrau’s signature. Further in “Painting Notes” he states: “I prefer having a voice over a style.” It’s a telling and strange comment. In what sense can a painting have a voice? Is not a voice the result of uttered or written verbal expression? “Why should a painter have a singular style,” he continues, “when they can have multiple voices? A cast of characters.” I differ with him here. I am unsure what kind of “voice” a painting can have—the power of pictures is their silence, the gaps left between any words that attempt to interpret or explain them. It’s certain, though, that his arrangement of paintings provides the semblance of a sort of metaphoric discussion. But I do see where a “voice” might emerge. Not in the paintings themselves (because how can a painting “speak”? its nature is silent) but in their arrangement, the way in which one painting is placed next to another. The juxtaposition between one stylistically unique composition with another one forces us to intuit what connections these two might have with each other. And that produces, in a metaphoric way, a conversation between them—that is, the “cast” of characters and their “voices.” In the case of these two paintings, one plays with two different kinds of opticality, depending on how you look at it; the subject matter of the other one shifts from abstract to representational when you read the title. As Bresson wrote, “A blue is not the same blue beside a green, a yellow, a red.”

The pleasure of looking at these paintings side by side is thus as much about what they do not say to each other as what they do. Something arises in that difference. Unrau’s painterly juxtapositions at first seem like playful contrasts, perhaps even a bit mystifying. Yet, the more time spent looking at them, the more they reveal, because Unrau’s paintings encourage us to consider looking as a way of thinking. They’re sort of not about anything, and they’re also about everything. They are about the way we look at the world, which is a way we think about it, and, in that way, maybe even something about who we are.

Aaron Peck is a contributing editor at Frieze magazine. His work has also recently appeared in The Believer, Walrus, The New York Review of Books, and The White Review. He is the author most recently of Jeff Wall: North & West.

Related articles

Closets/Containers

On Two Recent Paintings by Jacob Todd Broussard

A Stand In For The Thing

In Conversation with Liam Crockard

Abstract Languages

An Interview with Lina Viste Grønli