For NADA New York 2022, Towards is pleased to present a two-person booth featuring new work by Maria Trabulo and Tristan Unrau.

Working across painting, sculpture, and photography, Trabulo and Unrau explore the role that images, and artifacts play in shaping both our personal and collective histories.

For Maria Trabulo, this has meant exploring the ways in which nation-states, museums, and other organizations use cultural heritage as tool to establish, maintain, and distribute various forms of power.

At NADA, we will present new works that expand upon her ongoing examination into the ways in which the production, preservation, and reproduction of images and cultural artifacts impact our collective memory. Working with various museums and archives, Trabulo mines their collections to develop new works, rejecting the myth of the “neutral” cultural artifact, and highlighting the ways in which these items have been, and continue to be used to advance certain political, social, and economic agendas.

In 2021 Trabulo spent time in the vaults of the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (National Museum of Ancient Art) located in Lisbon, PT. Founded in 1884 to exhibit the collection of the Portuguese Royal Family, the encyclopedic museum is one of the largest in the country, with a nearly 40,000 objects in its permanent collection. In the 1960’s, the museum underwent significant expansion under the dictator António de Oliveira Salazar and his “Estado Novo” regime. As part of the expansion, new vaults were constructed to house the growing collection. At the same time, the museum became increasingly nationalistic and focused on presenting a narrative of Portugal as a colonial and imperial power that needed to be restored to its former glory.

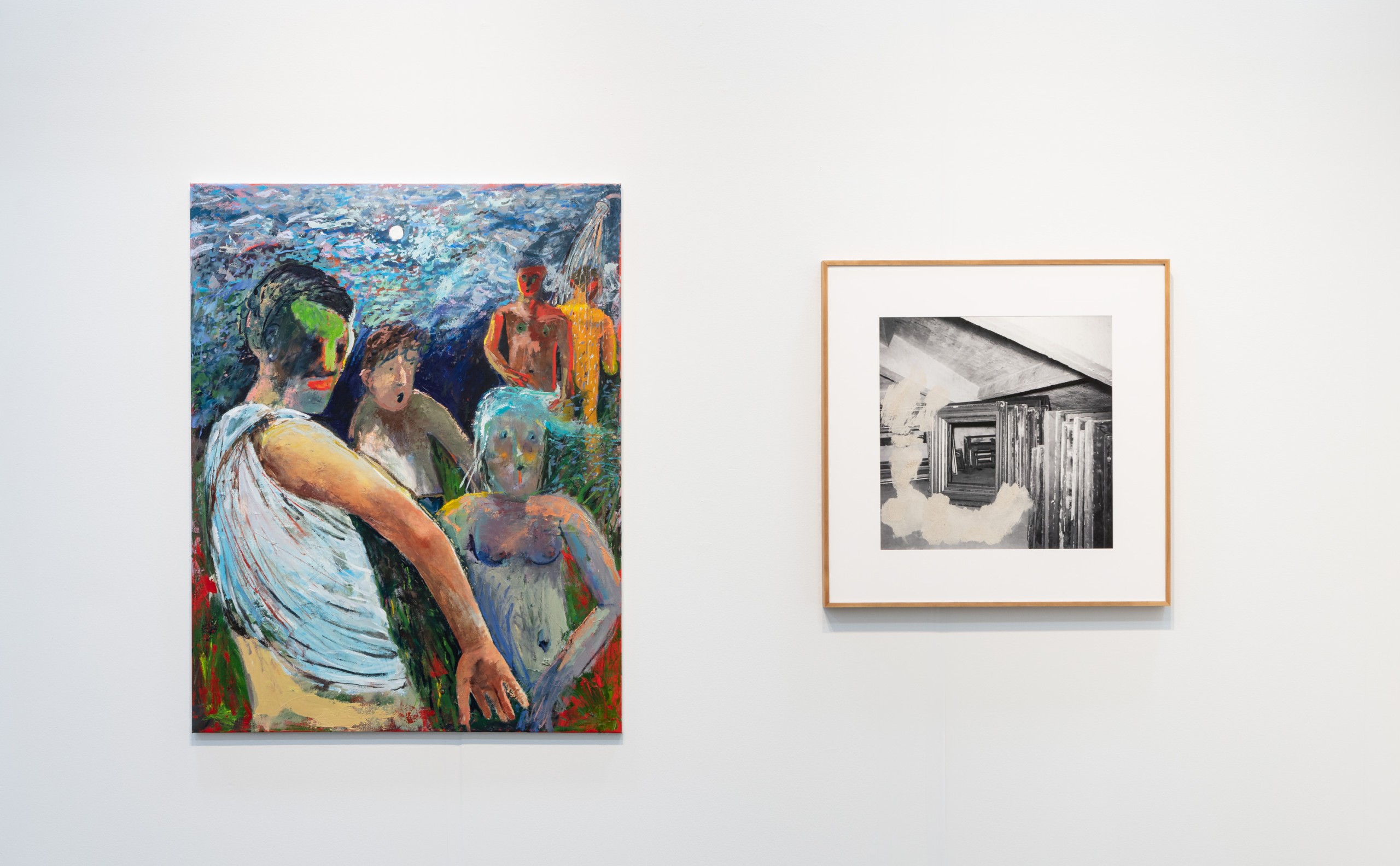

During her time at the museum, Trabulo developed a new body of work titled Collecting Dust. Comprised of both photographic, and sculptural works, the pieces within the series combine physical debris Trabulo has collected from the archives and merges it with historical elements from the museum. The four photographic works on display, are comprised of archival images of the empty vaults, taken during construction in the mid 1960s. Trabulo combines these historical images with particles of dust, wood, and stone that she has collected from the now overflowing storage spaces.

The sculptural works were developed from graphic shapes found in the first catalogue the museum produced in 1882, two years before the building would officially open. Trabulo selected the stylized framing devices as a way to highlight the intentional and inherently subjective act that goes into any form of selection and presentation of objects. This collapsing of time, space, and material, highlights the complex histories embedded in both these institutions and the artifacts they care for.

Tristan Unrau shares Trabulo’s skepticism towards meaning as some sort of fixed entity. Known for an expansive practice that does not privilege any single genre of image making, Unrau draws upon art history, cinema, philosophy, and personal experience to create richly layered and highly associative works – exploring such universal themes as the passage of time, love, curiosity, playfulness, and sorrow.

The four new works presented at NADA – while vastly different in both style and subject matter – suggest an investment in a particular experience across different kinds of painting. For Unrau, the idea that he would have a singular voice or be constrained to one form of image making is antithetical to how he approaches his practice. For him, painting is very much about creating a certain type of phenomenological experience, one that cannot accurately be described by language, but challenges a viewer to slow down and reframe the very act of looking.

Like much of Unrau’s practice, the works shown here draw upon art history, personal experiences and Unrau’s deep love and reverence for the act of paintings itself.

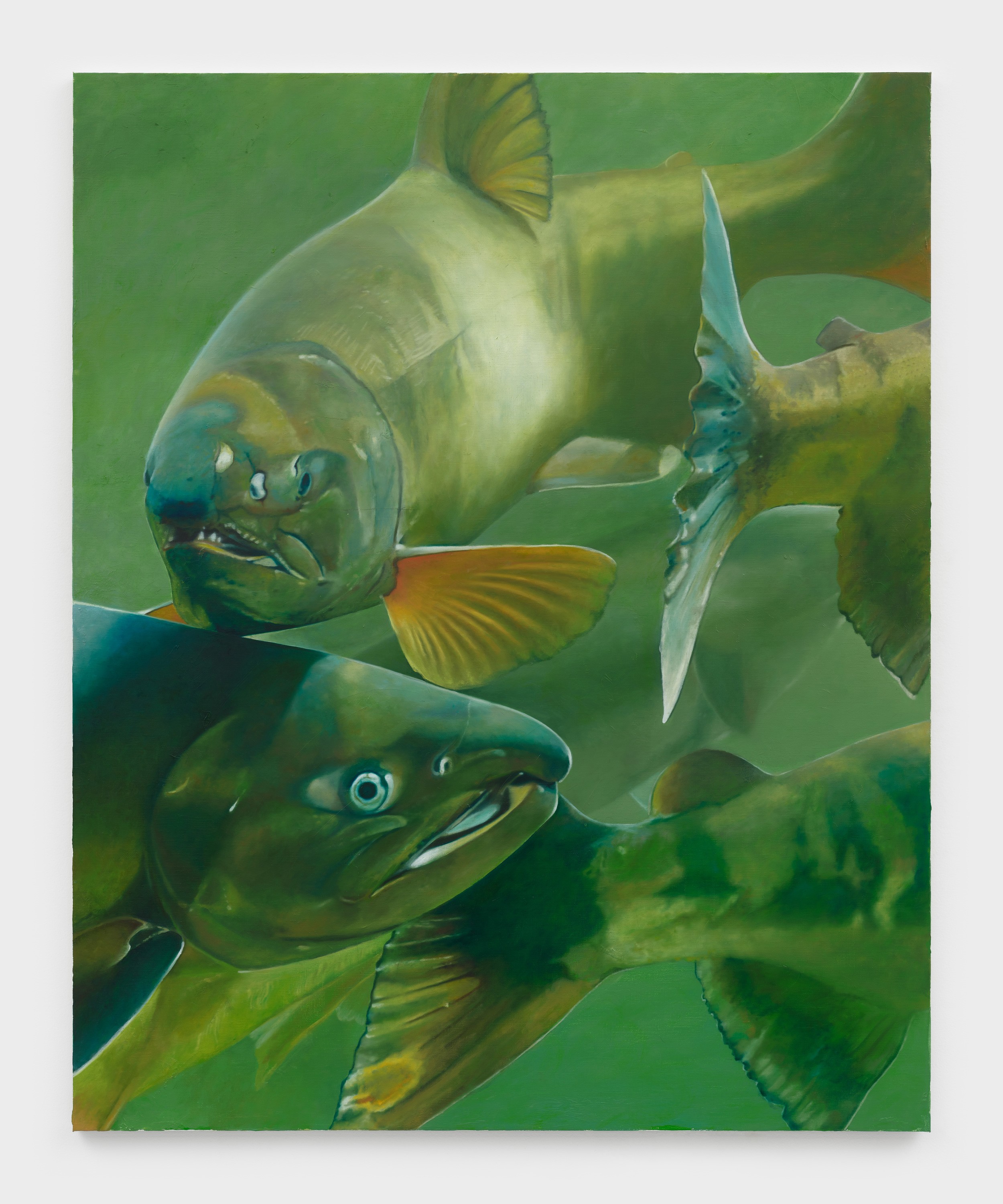

In World Weariness, Unrau turns his attention to the natural world and painstakingly renders an underwater scene of Chinook Salmon. Inspired partly by New Dutch Herring (1982), a seminal work by Dutch artist René Daniëls, Unrau uses this piece as a point of departure, and then formally, works in almost direct opposition to it. While Daniels’s painting is a loose study, with broad swaths of colour and seemingly slapdash brushstrokes that depict a school of Herrings cannibalizing each other, Unrau’s highly detailed, near photographic image of salmon becomes a deeply considered study of light and composition.

With If I had a hundred years, Unrau directs his attention to his more immediate surroundings. The painting is based on a sun-faded poster outside a restaurant near a friend’s studio in Chinatown, Los Angeles. Struck by how the natural elements had transformed the image over time, Tristan decided to reproduce it – rendering its sun softened, muted palette in a sincere and expressive manner, one that is much more reminiscent of Monet and the early Impressionists than 21st century downtown LA.

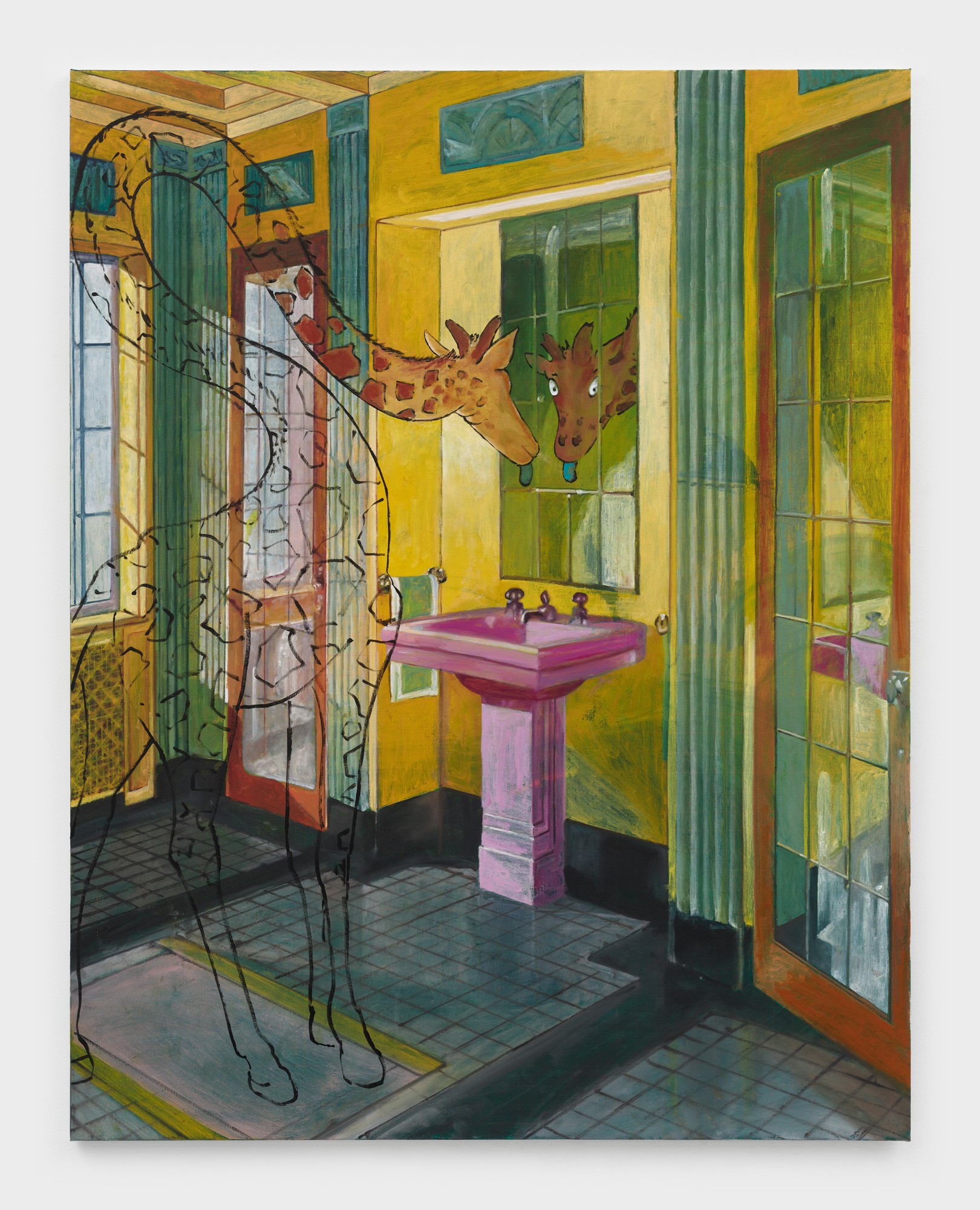

In Interior, portrait, Unrau ventures from the earnest and sincere, into the comical and the absurd. A well-appointed bathroom is thrown off by a large giraffe gazing incredulously at itself in the mirror. While the bathroom and Giraffe’s head are fully realized, as you move down the giraffes’ neck, it devolves into a simplistic black outline drawing. While certainly amusing at first glance, upon further reflection, the painting can be read as a commentary on the act of looking, and the potential of self-realization that can only come through careful and considered observation.

Five figures returns Unrau’s focus to art history and significant painters from the past. The piece is a direct tribute to the late Bay-area painter David Park. Unrau references different figures from across Park’s body of work, merging them into a new composition and adding elements of his own in the process. In Unrau’s composition, layers of paint are built up through short staccato-like brush strokes. The figures twist and turn around what appears to be some sort of moonlight gathering. Like many of Unrau’s works however, there is a level of ambiguity to the painting, leaving it up to us, the viewer, to fill in the missing story.

Viewed together, Trabulo and Unrau’s works can read as a study of opposites of sorts – of absence and presence; of personal and collective histories; of sincerity and absurdity; and of the ever-evolving ways in which we seek to create meaning. At the core of their practices however, is an important reminder, about art’s unique capacity to help us reimagine the world.