Towards is pleased to present The Window and The Frame, an exhibition featuring work by Rosario Aninat, Dylan Macaulay, Simon Shim-Sutcliffe, and Maria Trabulo. The exhibition examines the construction of both images as well as physical space. Spanning photography, sculpture, and collage, the exhibition explores themes of interiority vs. exteriority, concealment vs. representation, art history, as well as the built environment.

In 1435, the Italian architect, artist, and general polymath, Leon Battista Alberti published his seminal treatsie Pictura (On Painting). In it, (amongst other things), he posited that a painting should function as an “open window onto the world…” Since then, countless artists from Vermeer and Matisse, to Duchamp and Sturtevant have used the window and the frame as both a pictorial device, as well as a conceptual framework to examine the most fundamental elements in the construction of images and notions of representation.

Simon Shim-Sutcliffe’s practice explores the ways in which architecture and the built environment interface with the “natural” world. Through primarily photography and installation, he highlights the ways in which cultures and societies impose themselves onto different environments.

The four photographs included in The Window and The Frame are part of a larger series, Impressions of sites unseen. Taken during travels throughout Europe and parts of South America, the images have an isolated quality to them, spaces that feel largely devoid of any human activity while simultaneously being filled with man-made elements.

On the surface, the photographs can be read as mere documentation – capturing a specific place at a specific moment in time. Upon closer reading however, the photographs become ostensibly about the very act of constructing images. Their deliberate and meticulousness nature address the fundamental elements of image production – questions of light, form and space; of framing, cropping, and editing; and of the eternal question – of what to include and what falls outside the frame.

Maria Trabulo’s multi-disciplinary practice examines the role that images and artifacts play in shaping both personal and collective histories as well as the political implications behind the restoration and replication of cultural heritage. Working with various museums and archives, Trabulo mines their collections to develop new works, rejecting the myth of the “neutral” cultural artifact, and highlighting the ways in which these items have been, and continue to be used to frame certain political, social, and economic agendas.

In 2021 Trabulo spent time in the vaults of the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (National Museum of Ancient Art) located in Lisbon, PT. Founded in 1884 to exhibit the collection of the Portuguese Royal Family, the encyclopedic museum is one of the largest in the country, with a nearly 40,000 objects in its permanent collection. In the 1960’s, the museum underwent significant expansion under the dictator António de Oliveira Salazar and his “Estado Novo” regime. As part of the expansion, new vaults were constructed to house the growing collection. At the same time, the museum became increasingly nationalistic and focused on presenting a narrative of Portugal as a colonial and imperial power that needed to be restored to its former glory.

During her time at the museum, Trabulo developed a new body of work titled Collecting Dust. Comprised of both photographic, and sculptural works, the pieces within the series combine physical debris Trabulo has collected from the archives and merges it with historical elements from the museum. The two photographic works included in The Window and the Frame, are comprised of archival images of the empty vaults, taken during construction in the mid 1960s. Trabulo combines these historical images with particles of dust, wood, and stone that she has collected from the now overflowing storage spaces.

The sculptural works were developed from graphic shapes found in the first catalogue the museum produced in 1882, two years before the building would officially open. Trabulo selected the stylized framing devices to highlight the intentional and inherently subjective act that goes into any form of selection and presentation of objects. This collapsing of time, space, and material, highlights the complex histories embedded in both these institutions and the artifacts they care for.

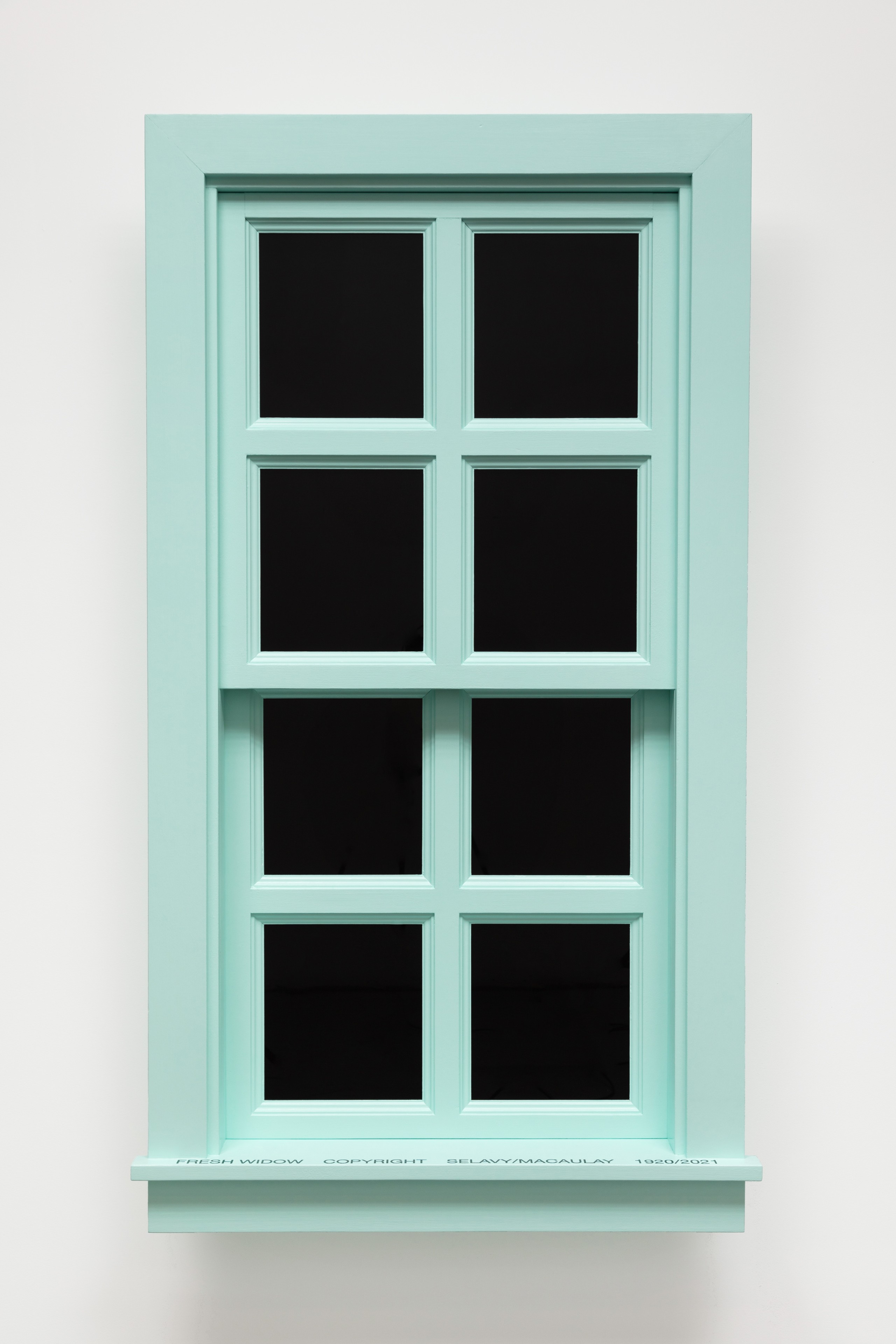

Dylan Macaulay’s For and After Rrose is an homage to Duchamp’s seminal work Fresh Widow. Constructed in 1920 after Duchamp returned to New York from Paris, the work was built by a local carpenter to Duchamp’s specifications. The title of the piece is a play on words – the style of window being known as “French windows” for their ubiquity in Parisian apartments, while also alluding to the abundance of recent widows following the devastation of World War 1. Fresh Widow also has the distinction of being the first work Duchamp ever signed as “Rrose Selvay”, his female alter-ego that he would return to many times over the course of his life.

In For and After Rrose, Macaulay takes the long lineage of Duchamp’s readymades and extends it one more time over. In his reinterpretation however, Macaulay makes a couple of important modifications. The first and most notable is scale. Duchamp’s Fresh Widow measures 30.5 inches tall, making it feel small, like a scaled replica rather than an actual window. In contrast, Macaulay’s For and After Rrose is nearly 66 inches tall, making it life size. Another key distinction is the backing materials on the windows. In Duchamp’s Fresh Widow, there is an opaque, black leather backing behind the panes of glass, of which Duchamp insisted be “be shined everyday like shoes”. In Macaulay’s reinterpretation, he has used lacquer to back paint the glass which is a commercial painting technique. This creates a reflection of the viewer, diverting attention to one’s own existence being reflected back to them. This purposeful mirroring deepens the viewers involvement in the work, allowing them to see themselves in the object and encouraging prolonged looking and contemplation.

Rosario Aninat’s practice is interested in the sculptural possibilities within mass industrial systems. Her work is characterized by both a material language and a way of directing one’s attention to the often overlooked. For her piece Moon, she zeroes in on a small detail from an important architectural site on the outskirts of Kyoto.

The Katsura Imperial Villa is a palace and set of gardens built between 1620 and 1647 for prince Toshihito. Widely regarded as prime example of traditional Japanese design, the buildings and its gardens have been an important site and inspiration for generations of both Japanese architects, as well as giants of 20th century modernism including Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius.

In Moon, Aninat has taken a small detail from the Katsura Imperial Palace and reinterpreted it. Derived from a door handle detail in the villa, the form of the sculpture is based on the Chinese ideograph for the same word (moon). Through a shift in scale and materiality, Aninat’s reinterpretation transcends its source material and evokes something wholly other. The work acts as a portal – focusing one’s attention and re-framing their experience