Towards is pleased to present For Example, an exhibition of recent work by Los Angeles-based artist Tristan Unrau.

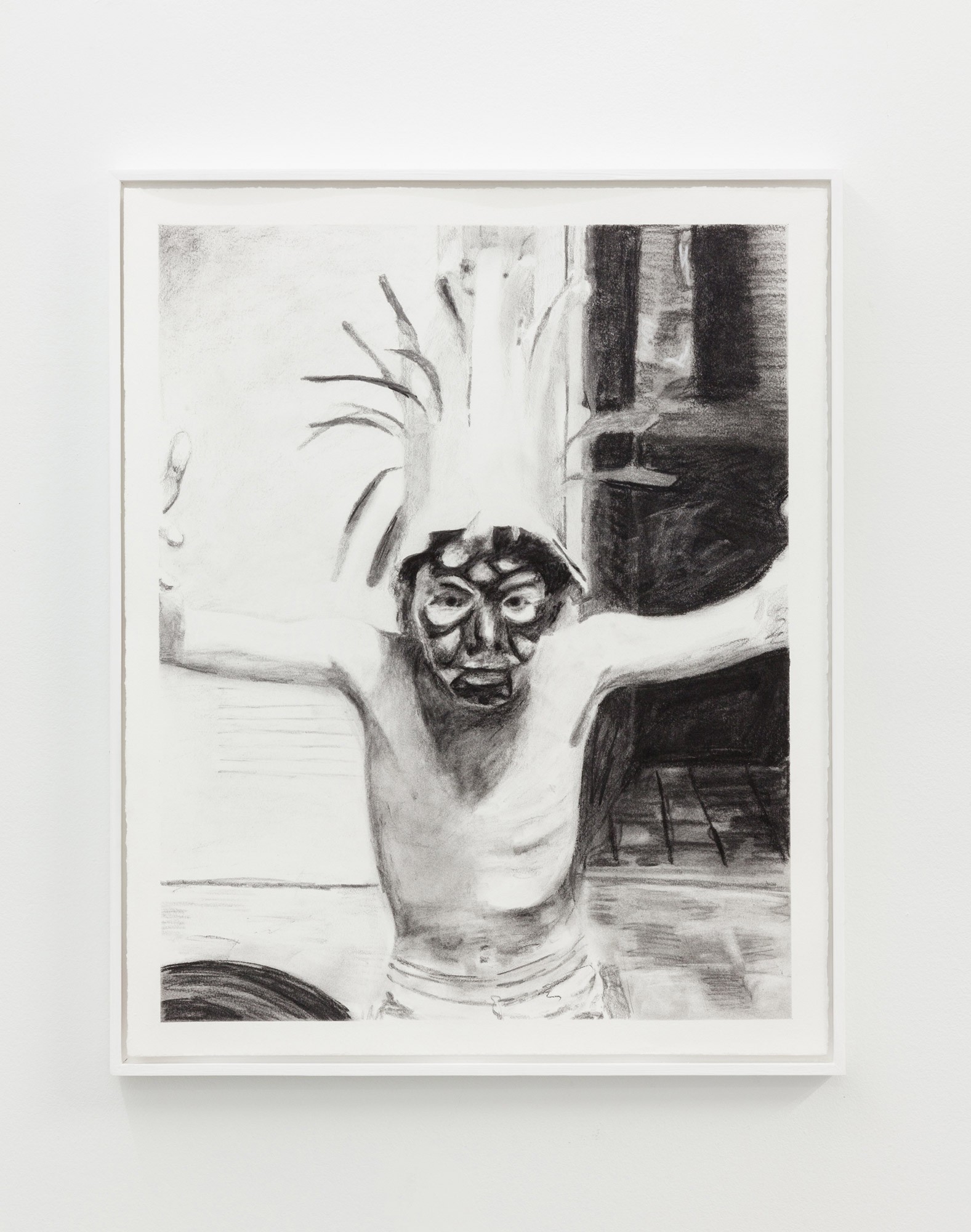

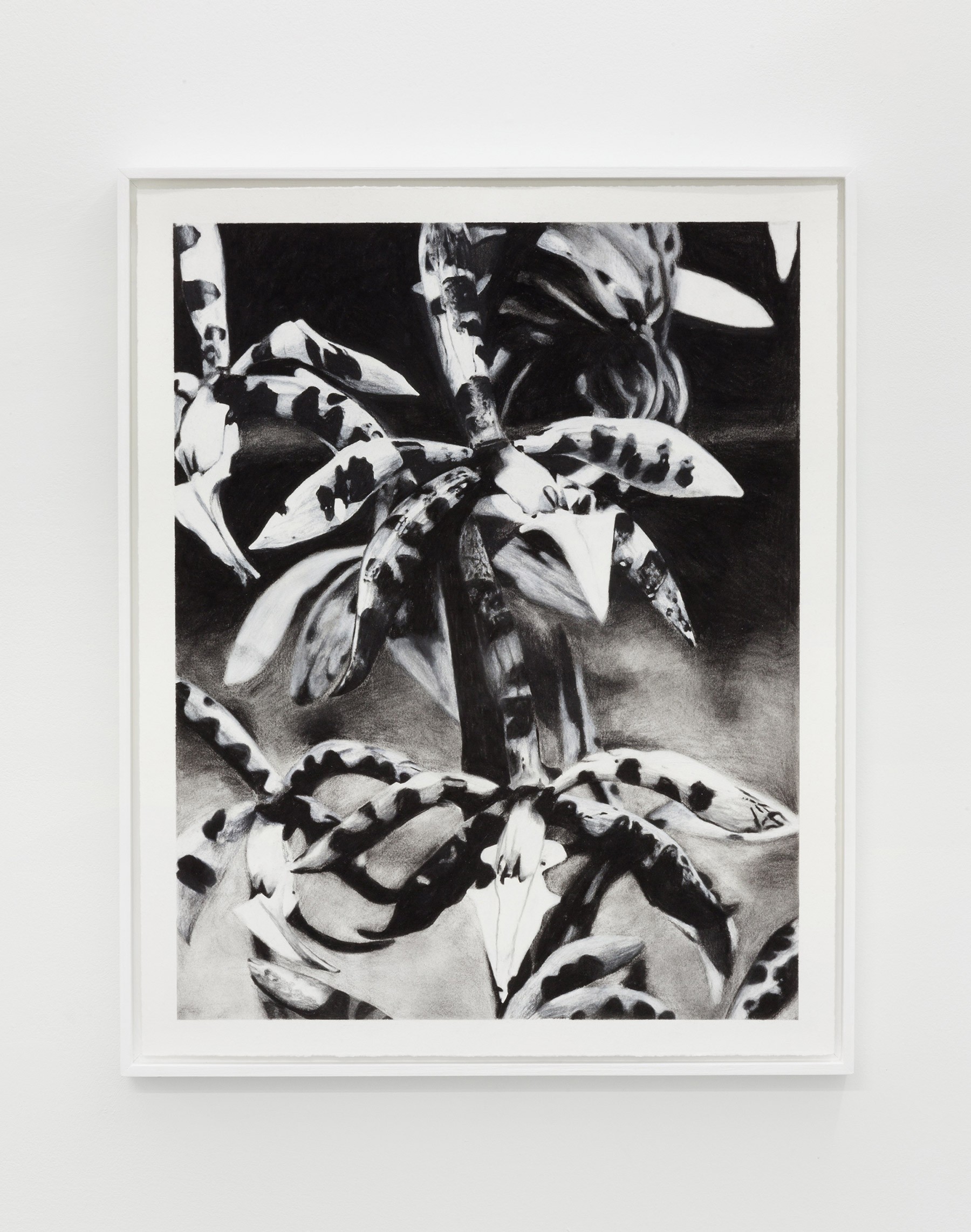

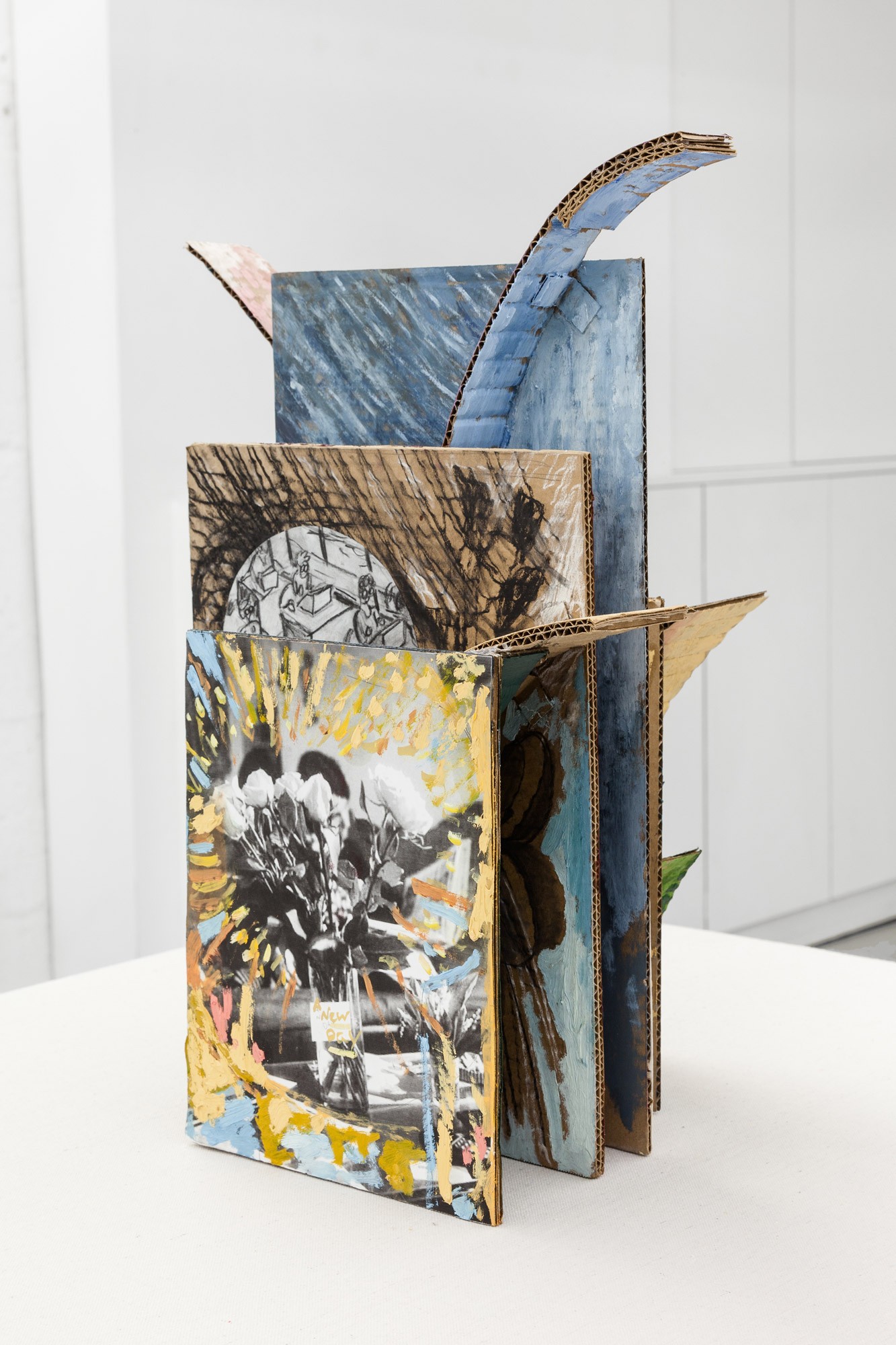

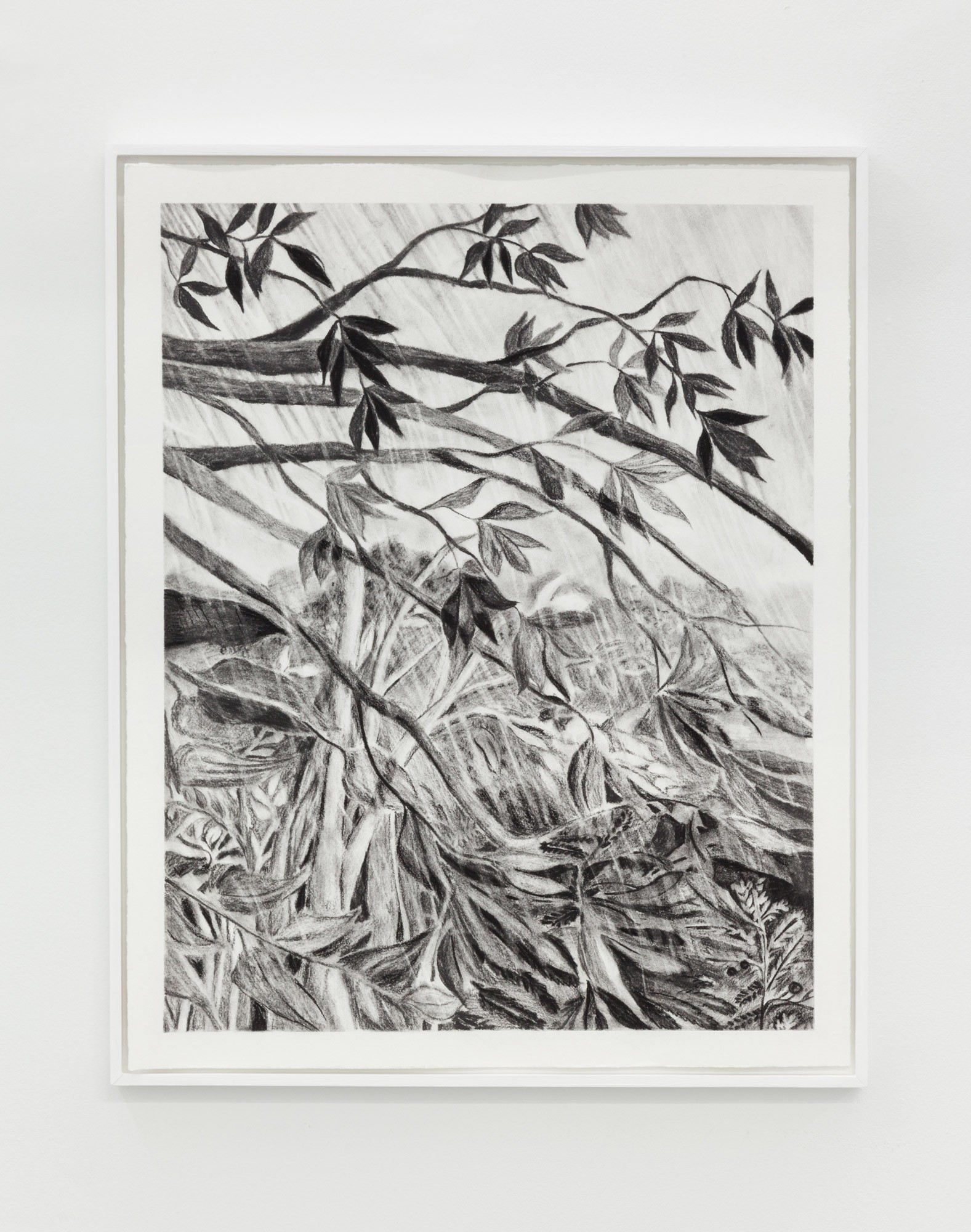

1. Strip them down to their essential parts. Stories distilled to pictures, excised from their context. Divest them of their colour — leave tone on a surface, lines on a page.

Yet still, sensuous comes to mind. Those abysmal blacks and undulating greys. Such nakedness can’t help but elicit a kind of want and suggest a sort of pleasure. The word sensuous, when it first appeared in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, attempted to avoid the sexual connotations of the sensual; but the association persists. Are these drawings also an effort at evasion? From references unknown, each image insinuates but does not reveal its history. It could be called an act of unification. Or appropriation. Mimicry too, adaptive and assimilatory. It leaves me suspecting that behind the gesture, an image, or this drawing, is a vortex of meaning I have missed - a nonsensuous withholding.

2. There is a picture of an orchid, perhaps leopard, if there is such a thing. Who could possibly know them all by name. There are over 25,000 species and 100,000 hybrids, orchids being among the oldest and most successful flowering plant. Botanists and biologist discover new and perplexing ones each year — ever smaller flowers, measuring only half a millimetre wide, and hermaphroditic ones that copulate with themselves exclusively. The flowers can smell like vanilla or rotting meat or nothing at all. They lure pollinators with material rewards but also practice mimicry — sometimes it is a simple deception, colour or scent suggesting nectar, recompense they do not in fact possess; other times it is more elaborate, nearly unbelievable forms of trickery, for example, the Ophrys Eleonorae, known commonly as the Bee Orchid, has a labellum which resembles the velvety body of a female bee, with a scent to match; mistaking it for a mate, male bees attempt to mount the flower and during the lascivious act the orchid stealthily stows its pollen on the bee’s back. Does the orchid know what it does? Does it owe the bee an explanation? Representation is a sensuous act — no need to tell the orchid or the bee.

I keep looking at these drawings imagining that they tell a story or contain some kind of wisdom. It could be right there at the surface, or hidden somewhere underneath. I stumble through a malformed hermeneutic cycle — like we, me and you and the pictures, are playing a game of telephone. Each iteration an adulteration — you take them from their context, re-present them here, I turn them into text and change them yet again. To what end? Perhaps I expect them to do or be things other than what they are. I want them to help me make sense of the world.

The Spanish Influenza killed between 50 and 100 million people worldwide, making it among the most deadly natural disasters in history. Unlike most flus, which threaten the young, the old and the immunocompromised, the Spanish flu had absurdly high mortality rates among robust and healthy adults. In perfect cytokine storms, their strong immune systems betrayed them, laying waste to once vigorous bodies.

What is the logic of such a thing?

I infer a vast and sentimental world from these pictures. A young woman looking out to sea at a future of possibility; a boy betraying the anguish of existence; swirling vortices which hint at tragedies to come; and nine little Optimists gliding across a page of placid water.

But interpretations say more about the interpreter than they do about that which they attempt to elucidate.

I have expectations and look for explanations. If the pictures do have a kind of knowledge, it is of an irrational sort, not of language or stories but something indeterminate, mysterious, and provisional. Let us stop fussing with all the formalities and just stand with them then, quietly or in conversation, with drink in hand or maybe not. The pictures don’t expect anything of us, this is their generosity. The ten drawings suggest another option, for us to give them our attention and thus our empathy. The pictures forgive themselves their non-sense and their naïveté, and so must we forgive ourselves and perhaps this world too.

— Exhibition text by Ryley O’Byrne