Flattening, Flipping, Inverting

Nadia Belerique in conversation with Aryen Hoekstra

In its contemporary manifestation the photographic image is most commonly understood as that ubiquitous descriptor, re-presenting representations in a correlationist’s house of mirrors. Alternatively though, if one begins simply with the photograph, its analysis reveals that it is itself a component of the world, and not merely some scaled representation. For Nadia Belerique this photo-object is a site of transference that provides clues to a world obscured, unveiling a vibrant energy noumenally transferred between silent actors. In our conversation she discusses her relationship with photography, analysis, and the potential blurring of identities that occurs through collaboration.

Aryen Hoekstra: I want to begin with your work The Counselor, which was shown twice this past year, once in Toronto at Gallery TPW and then again in Vienna at Kunsthalle Wien as a part of the ‘Blue Times’ exhibition curated by Amira Gad and Nicolaus Schafhausen. The councilor in question is actually Deanna Troi, the half human - half Betazoid empath aboard the Starship Enterprise. I’d like to start here because I think — at least recently — the idea of counsel has taken a central role in much of your work.

Nadia Belerique: Well, I’d been in psychoanalysis at the time of its making for about 4 years and that had always been in the background of what I was thinking about in my studio. So although most of my analysis centered around the relationships in my life at the time, while I was in grad school I started to shift the attention of these sessions onto the subject of my practice, asking whether or not I was displacing these relationships onto my work. At a certain point though I became distant enough from both of these things that I was able to start to think about analysis more generally. Analysis of the image, analysis of art, but also analysis of the self. Really though, it’s quite deeply personal because my experience of analysis was always that I would talk and talk and talk, and nothing ever came back. My analyst’s role was such that he was always listening, but never responding. So there was this process of transference that would occur, which just boils down to the idea that things get displaced. When I think about a photograph, I think about things being displaced onto this object.

The photograph?

Yes, the thing that it’s representing for example. At that point a lot of things converged. I was interested in a photo-object that could ‘feel’ like something, something with a physical presence.

A photograph that felt like an object?

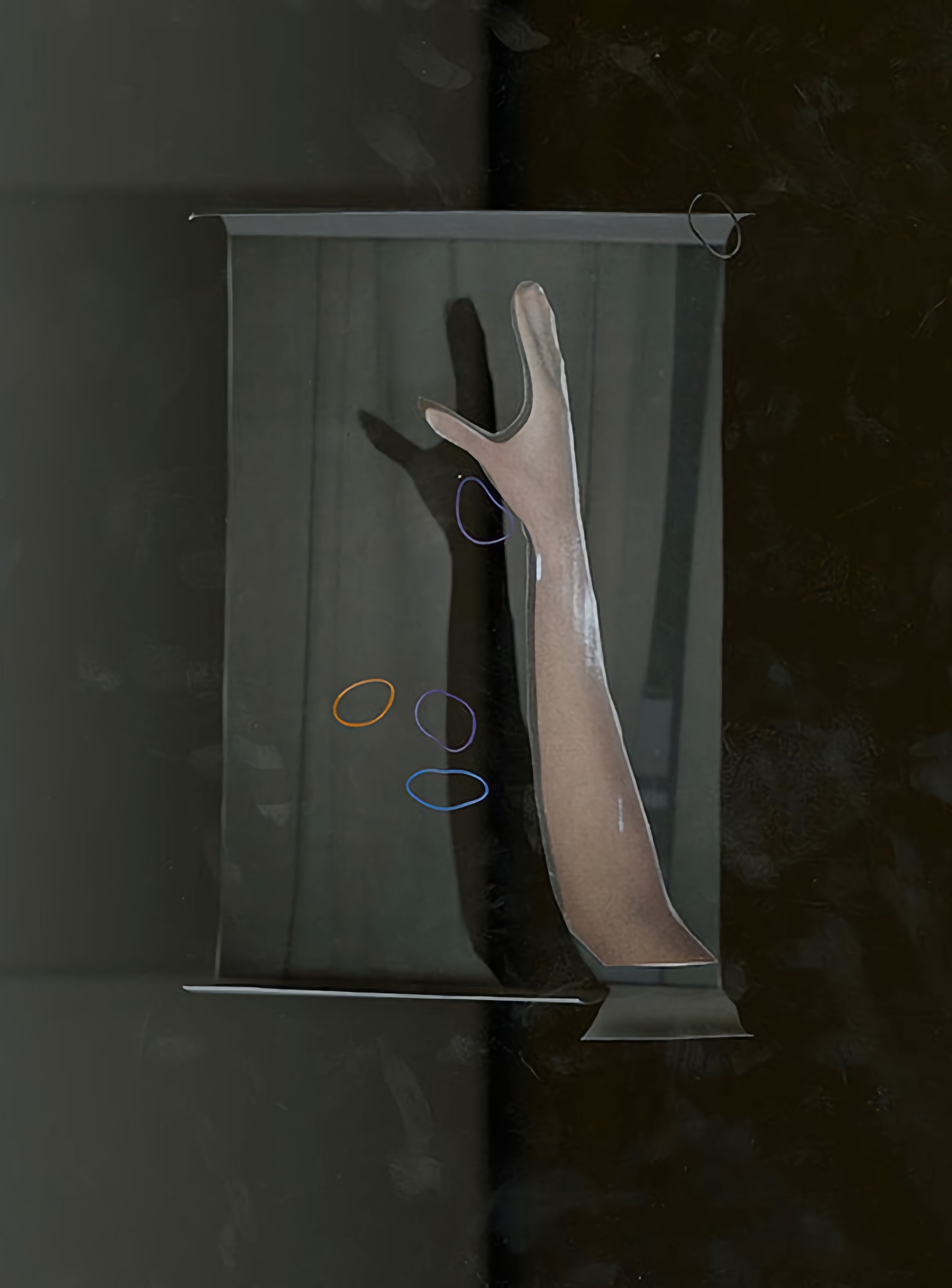

But not just an object, a person. I’ve always been interested in a 1:1 relation between the photograph and what it depicts, things representing things that were to the same scale. I wasn’t necessarily aware of how it was all making sense at the time, and this is somewhat in retrospect, but, basically I became obsessive about these cardboard cut-outs. Mostly this was for their photographic quality, and especially the documentation of these cut-outs online. That really came through my research, ‘What do these things look like?’, and of course there are people taking pictures of these cut-outs to sell online. So I was just looking at these objects as pictures. How do they translate as images? Can I get a sense of them through their documentation? It’s a double removal. It’s not the person, and it’s no longer even the cut-out. It’s a photograph of the cardboard person, which provides a really interesting experience.

So when did you decide to cast Deanna Troi as the protagonist?

At first I wasn’t really concerned with the identity of the cut-out, but in these image searches my screen became filled with Star Trek TNG characters. Growing up I was a fan of the show, so it caught my eye just based on that. Also it made a lot of sense to me in that this is so of its time, the 90s or late 80s, when these cardboard cut-outs weren’t yet passé. Then, of those characters Deanna Troi was perfect, because

- She was my favourite character

- She looks like me in this really generic way, and

- She's this empathic being and embodies the idea of feeling.

Not only is she a counselor, she’s an empathic counselor, and as I’m thinking about how a photo-object can have a presence, or exude a feeling, these parts were all fitting together quite nicely. It was then a case where her identity was actually contributing to the work, which is much better than something arbitrary. So ultimately that was the figure that the work had to be.

And this feeds back into your conception of the photograph as a site of transference.

Exactly. I was thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting to have this counselor who doesn’t have to say anything?’ She can just stand there, which was my experience of analysis already. So you could ask something of the artwork, present a question or query, and it’s going to give you something, but only through this transference of experience. A feeling rather than language - which has always been a point of contention for me as an artist, where language isn’t my primary mode of communicating, it’s visual. So the visual translated into experience, in front of a “person”, in a symbolic way, in an actual way.

Inkjet photograph mounted to aluminum and plexiglas. 20″ x 28″.

So this encounter, although the photograph is the catalyst, it’s an affective relation that takes place outside of what we would consider to be the realm human perception.

Well I think that The Counselor suggests that perhaps it is, but for me this is actually just the idea of being a woman. It falls into the realm of intuition, and I’m not saying that this is found only in women, but to me there is something spooky about people. As I was starting on The Counselor it was also at a point where I had the thought that I would make my feelings into useful content for my work. Feelings that are just as present as an object might be, but that are harder to perceive with the human senses we have. When you talk about spaces between objects, or between subjects for that matter, I think this is an interesting threshold, because I actually do think there are a lot of things going on that we can’t see. This is why I am trying to bring as much attention to that space surrounding an object as I am to the space that you’re meant to be looking at. The work I produced for Tomorrow Gallery is an example of this.

When you talk about spaces between objects, or between subjects for that matter, I think this is an interesting threshold, because I actually do think there are a lot of things going on that we can’t see.

At Tomorrow, those two works were installed in such a way that their profile becomes a third sculptural space.

I really like the gesture of them both glancing over their shoulders. They look very suspicious as if they might be hiding something, and yet there is actually much more being revealed. Their silhouette gives them away, like the profile of a face. It’s a revealing moment. I’d done a project, Risky Rhythm, at 8-11 in Toronto that similarly had two steel sculptures, but those were really sandwiched in a tight space. So together they still only made one image, almost as if they were against a blue screen, but an inverted blue screen. At Tomorrow, they are set further apart, yet through their profile they are more engaged with each other as a sculpture.

It’s as though you’ve introduced a third axis into the equation. These flat sculptures are now asserting themselves as 3-dimensional.

Well now there’s more than one view. It’s a human body. It’s also a face. Now it’s a vase.

The back-and-forth, inside-outside inversion, is a recurring theme in your work. Is this something of a generative methodology for you?

It’s a game that I like to play with myself. It too has this metaphoric quality that speaks to how I feel about a lot of things, and one that really strikes to the heart of how I think about photography. When I say inversion I mean this really basic positive/negative flipping that occurs when you look at a negative and the colours are reversed, which is not to say that I look at the world through an inverted lens, but it is something that I keep doing in my work; flattening, flipping, inverting.

I think the first time I really took notice of this flipping was in your exhibition Have You Seen This Man? (2014)

It’s funny, because me even saying, ‘Have You Seen This Man?’, is already an inversion, because I’m actually just talking about myself. This missing character, the photographer, is of course me, but then the ‘photographer’ too just seems to be the perfect emblem for a missing or absent person.

This character also allows for a narrative to build over the course of multiple exhibitions. You’ve said that you thought of your following exhibition, I Hate You Don’t Leave Me, as the revisiting of the cold case of the missing photographer. This is at a moment when there has been a sort of widespread investigative impulse in popular culture. The Serial podcast and HBO’s the Jinx being two recent examples.

I think the idea of the detective right now makes a lot of sense. We have access to all of this information, it’s really quite unprecedented, so now we have the opportunity to go back and find new answers to old questions. My impulse is more personal though. I like images that come from a particular time, and I like subjects that come from a particular time. I think this is because it really is impossible for me to detach my sense of understanding of the world from those first existential thoughts I had growing up in the 80’s. I need to revisit this time where I was being awakened in many ways, creatively, sexually. All of these things charge the work for me in a really powerful way. It adds this really psychological dimension to my practice. It’s as if I’ve flattened time or channelled a younger version of myself, one that was really just starting to learn about my own head.

Well, this psychological dimension of your practice is really why I wanted to start with The Counselor, because I think this is actually a critical entry point in understanding much of your recent work.

I might consider it a good vantage point to consider my work from, but to me it feels like there is a bit of a disconnection there, because going forward there is no more Star Trek. What The Counselor does establish though is that I am asking the viewer to consider my work both literally and metaphorically, and really both at the same time. Seeing what I can get away with.

You’d mentioned something to me the last time we spoke that might relate to this, which is that you had this impulse to shift your practice away from employing a cinematic narrative, to one that is literary. A lot of the ‘psychological’ that is present in your exhibitions, which is really a great strength of yours, is through this mise en scène staging that occurs. What does this literary shift look like?

I think it comes through leaving information out so that a viewer has to put things back together themselves. There’s something very powerful about not showing something. Also, when you’re reading as opposed to viewing there’s this sense that you’re listening to someone speak and you can almost say all the words along with her. It’s a very active form of anticipation. You’re making it as you read it and it’s all taking place in this mental space. You’re literally making all the words come, illuminating the words, and all of this is occurring in your head. Whereas in film it’s more passive. There is only one step to connect as you’re constantly looking at the image. At least these are the terms I think in when I make a photograph. Its object quality itself is like a book and the image is more of a screen.

When you’re reading as opposed to viewing there’s this sense that you’re listening to someone speak and you can almost say all the words along with her. It’s a very active form of anticipation.

And so you’ve shifted the emphasis of the photograph to its status as an object.

Photography in general and how it was shown for a very long time is very boring to me. It always struck me as paradoxical to try to do something that’s both fixed and very representational at the same time, and then to say, “No, it’s not about any of that. It’s not fixed and it’s not representational”. This has larger psychological implications, as it results in multiple identities. The title, I Hate You Don’t Leave Me, comes from a self-help book about borderline personality disorders, which to me is fitting in that it’s a disorder where you can’t see the line between things.

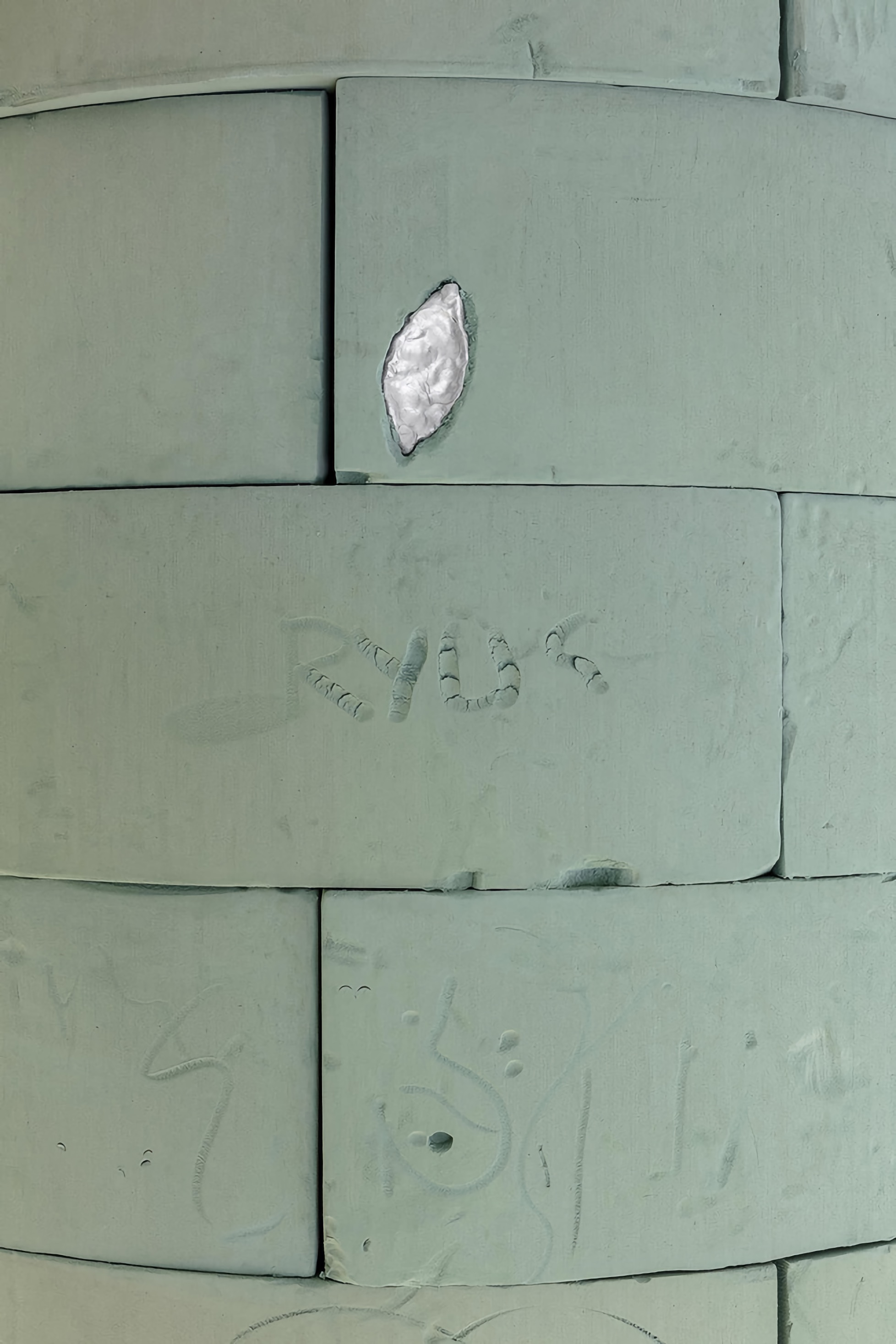

Another project with psychological undertones was Don’t Call it a Breakdown, Call it a Breakthrough, a show you curated last fall with Lili Huston-Herterich. You just finished working with her again and with a third artist, Laurie Kang, on a collaborative work, The Mouth Holds the Tongue, for the Powerplant in Toronto. You all have separate solo practices, so what was it that brought the three of you together?

We’ve all been working together tangentially for some time. Lili and Laurie connected through a panel they were both on, and Laurie and I did a small collaborative work for Art Metropole and have been talking through studio visits for over a year. Then Lili and I curated that show together, but all three of us have always shared ideas about photography with one another.

This collaboration was taking place while you were making the work for Tomorrow and I Hate You Don’t Leave Me. Was it easy to move back and forth or was it necessary to keep that line between things?

Well this was definitely a fourth practice, not a hybrid, and it took a lot of emotional energy. It really ended up taking centre stage for all three of us. At first I think we each thought of it as a side project, but it came to be that we were making something bigger than any of us would be able to make on our own. It was especially a challenge because we weren’t making objects either; we were making a room. That might have been a strategy to avoid having to fuss over really discrete details. Just imagine three people making a painting; it’s a bit messy.

When you’re working by yourself it’s very easy to follow your own wonder and let your interests lead you where they may. I can see this being a challenge when you bring together three personalities who are typically free to roam, and then ask them to make something singular. Were you still able to find a way to communicate your ideas to one another or did you have to invent a new way of working?

It’s such an amazing experience to work with two other women who are both artists that work completely differently than I do, but then to come together to make this one thing. When you’re working alone in the studio you’re not expected to have to talk about the decisions you’re making, but in the course of our collaboration there was so much talking involved, more than I’m even comfortable with. It’s like we were three directors, and it definitely felt as big as a movie, and everyone is fairly adamant about what they want said. It’s all about negotiation, and sometimes we were all on the same page, and other times two of us are on one page and the third is somewhere else. So we’d have to sit there and convince the person with words about how this makes the most sense. It’s a really interesting exercise to make someone visual have to communicate with language. I’m actually pretty bad at it. Sometimes I would just through out phrases like, ‘you know?’, and other times I’d just show them pictures. I’d send them images of what I’m thinking about. They both think that I don’t know how to speak. They think I just speak in photography.

All images appear courtesy Nadia Belerique and Daniel Faria Gallery.

Aryen Hoekstra is a Toronto based artist and writer. In addition to his practice, he currently serves as the director of G Gallery.