A Stand In For The Thing

In Conversation with Liam Crockard

Over the past year Towards has been working in collaboration with Liam Crockard on an ongoing project. Through a series of informal meetings, we’ve explored a number of topics, from scraper bikes and blue collar aesthetics, to dematerialised labour and the role of humour in a contemporary art practice. While at times seemingly disjointed, these discussions have coalesced and what has emerged out of this process is an extensive course reader, compiled by the artist.

Through a combination of sourced texts and original collages, Crockard takes the viewer on a discursive path. Like the informal meetings that gave rise to it, the course reader can seem indirect upon first impression. Rather than present ideas in a didactic manner, Crockard prefers to circumanavigate a concept, talking around it and letting the viewer draw connections for themselves. Upon closer reading however, the course reader reveals an underyling structure and delves into many of the themes that that have been central to Crockard’s practice for much of the past decade.

Towards is pleased to present the course reader, and accompanying interview below.

I think a logical entry point to begin discussing this project is labour, and ideas surrounding the notion of ‘work.’ Both of these elements have been re-occuring themes in your own practice as well as a sort of organizing principle for the course reader itself. Can we talk a little more about labor, your personal relationship to it, and how you explore the concept within your practice?

My first major body of sculptural work started as a portrait of my hometown, Kitchener, Ontario. Through research I realized there was a pretty significant economic downturn and shift away from factory-made goods in the years before I was born. Memories that I drew upon as strictly personal reflections–helping my dad improvise a fix for a flooding basement, working in a factory during the summers between my undergrad, getting stoned in abandoned parking lots–were a direct result of certain economic conditions, in which the traditional notion of manual labor permeate all decisions. Perhaps because I kept returning to my hometown to fabricate work (which is only now experiencing an economic resurgence as a major tech centre in Southwestern Ontario–a whole other complimentary and conceptually rich avenue), I felt unable to insulate myself from those conditions and began to look at their root causes and the fallout as it effected both working-class and artistic communities.

It’s important to address the notion of material honesty in my practice as well. I came to sculpture and conceptually-driven works through my ongoing practice in the medium of collage, in which my interest has always been more couched in the notion of accumulation and organization of materials rather than their outright transformation. This stems from a real belief in the integrity of materials, and my desire to subject them to processes that seem contextually appropriate, but not necessarily proper. I have no issues with abusing a material, destroying it, repurposing it—but generally those decisions are made in accordance to what a material “does” and subsequently what it shouldn’t be doing. There’s a recent interview with Christopher Williams on DIS where he quite talks about something exceeding its descriptive function and entering into the realm of the poetic. I like this idea of pushing something beyond its logical use until it almost unwittingly becomes a more interesting statement. I’m a bit of a slacker-structuralist I suppose. Ultimately, you see my interest in material formalism and nostalgic working-class history collapse onto each other under the constructs of modern work: deadlines, budgets, material restrictions, deskilled labor and so on. These can be adapted as working methods, theoretical positions for arguments or something to joke about.

You’ve spoken about material honesty and the concept of transparency within your practice. I think these are two ideas that especially on a formal level, are quite evident throughout the course reader. Can you expand on your decision to use the scanner bed as well as some of the other formal choices encapsulated within the reader?

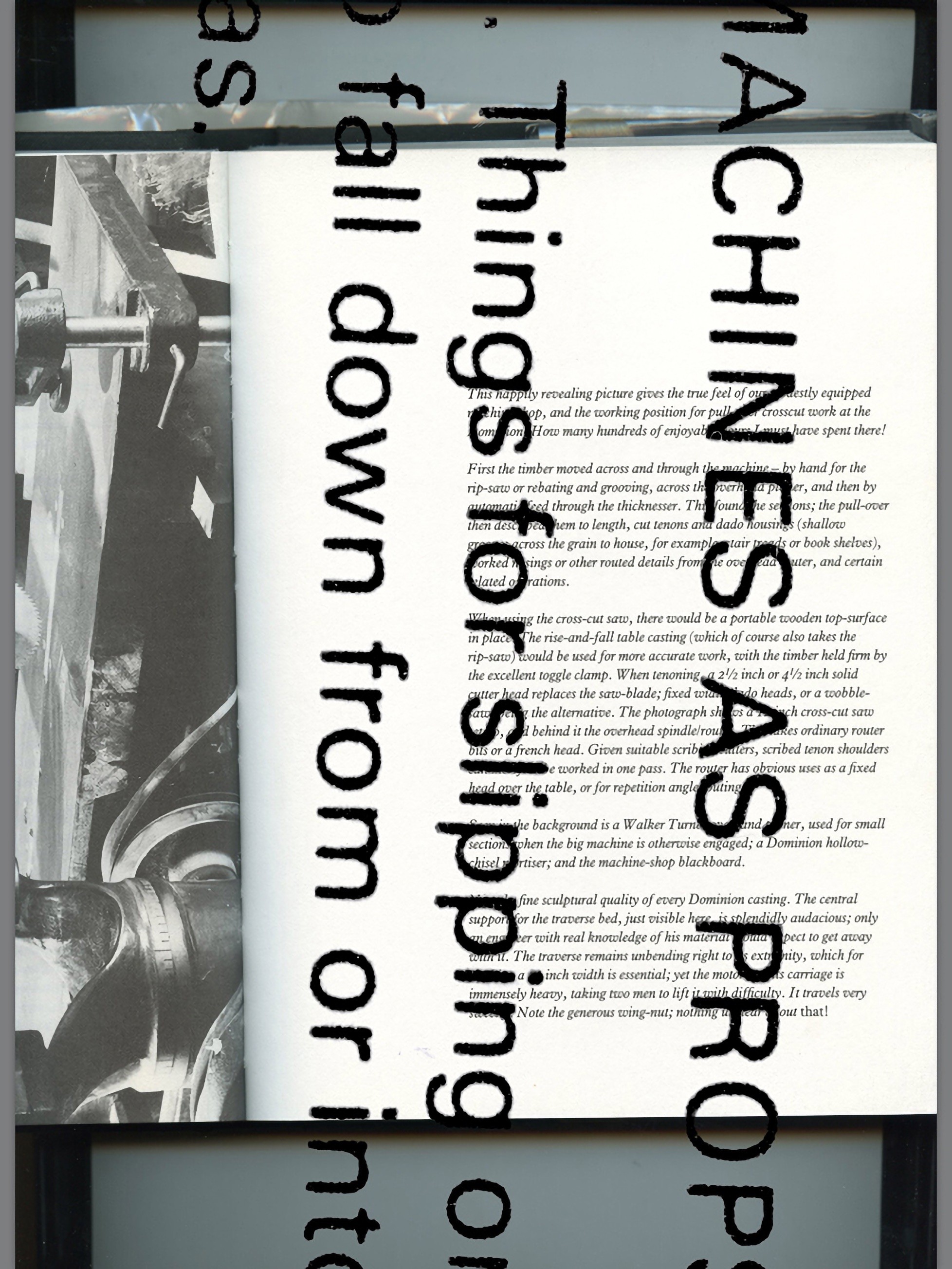

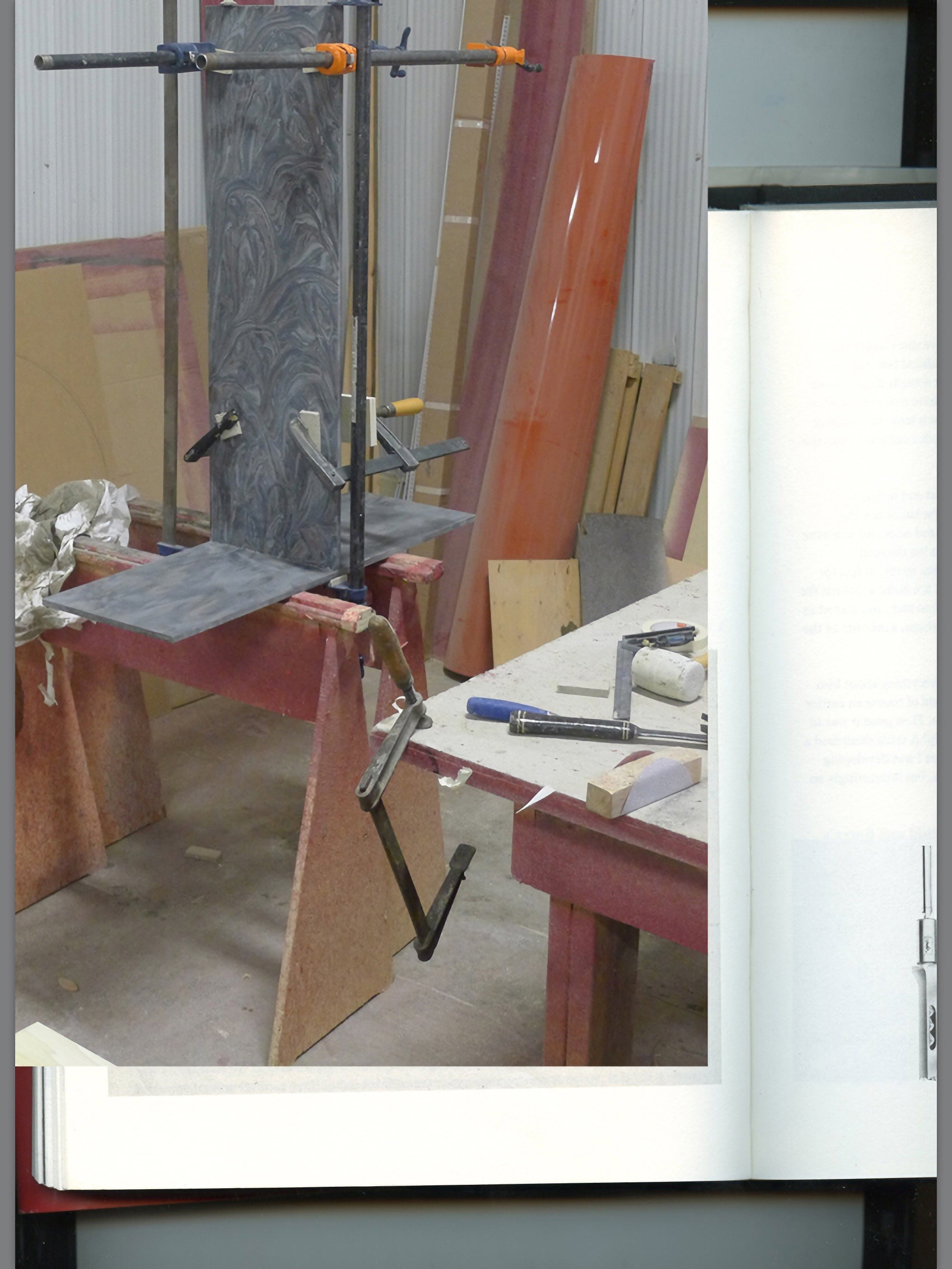

When we first started talking about this project the idea of something materially-driven for the web was a real sticking point. I was interested in developing a project that couldn’t really exist on another platform. The first iteration of the course reader was a similar concept but was made using content run straight off of a photocopier. This was to accompany a solo exhibition in lieu of a formal essay or statement, so that kind of immediate, tactile gesture made sense. I knew I wanted to makes something that could be freely disseminated, and that existed in an equivalently “tactile” state on the web. Scanners are great because, like photocopiers, their construction insists on a gesture of flattening, both through its perfect lighting and clamshell-like design, and when you overwhelm the technology by putting too much on the bed, or not enough, or if the object is too thick, these flaws become so immediate and exaggerated. It is quite easy to overwhelm the machine and reveal its own materiality.

From here, it was really about limiting my design decisions with some self-imposed restrictions, both to further emphasize the conditions of the scanner and to simplify the process. For example: there’s only ever two images used on any given page, all images exist in their original size, cropping only occurs as it is dictated by the frame-size of the scan bed, et cetera.

Additionally, all non-scanned images are fragments of previous projects as they might relate to the content. I thought it would be a nice way to suggest some eventual physical resolution for a lot of the ideas raised by the text, or vice versa.

I think a lot of artists relate to the way how art and research revolve around each other and spin off into new ideas, revisions, negations, and occasional total oblivion.

This question of materiality to me is a very interesting one. From the outset of this project, we spoke about creating something that was very “web specific,” in the sense that both its content, as well as its form, were created with a screen in mind. While I think you’ve succeeded in doing that with the Reader, there is an interesting paradox that arises. The scanner plays this dual role of both flattening these objects into a one dimensional image, while simultaneously making you hyper aware of each books individual physicality.

In this sense, the pages of the reader seem to almost take on the role of props. They are imbued with meaning, yet the scans are stand—ins, facsimiles of the “real thing.” How do you see this idea of the prop relating to your overall practice?

Generally, with regards to making semi-functional objects—things that seem to invite some kind of interaction—I turn again and again to the role a prop plays on stage, insofar as there are rules and different levels of interaction implied based on your role in the theatre/gallery. Primarily we look at props as lending context to a performance, but the opposite is also true, particularly as the stylization of the stage production becomes increasingly abstract and consequently privileges a smaller or more dedicated audience. Actors can imbue simple constructions with elaborate stories or powerful symbols by virtue of a narrative or set of gestures. There was a kind of high-water mark with excessive and representational scenography and prop design that was largely shook up in European theatre during the period of Constructivism. As a desire for more humble, socially oriented productions passed through a filter of the avant-garde, there was a stronger reliance on performers and audiences alike to activate the work. Even Western European and North American theatre changed in some regards, particularly in the construction of theatre houses, which no longer privileged a one-directional or amphitheater-like design and instead allowed for or other more experimental audience-stage relationships (Interestingly, it is thought that the earliest deviations from these classic designs came from modern Japanese Kabuki, in which there are multiple staging areas and the audience is stuck somewhere in the middle).

The parallels between this architectural shift and that of the modern museum/gallery seem fairly clear, especially considering Antonin Artaud’s manifesto1 that followed Constructivism, in which he called for a theatre with no boundaries or demarcation for performance at all. Of course the reality of this utopian ideal calls for social conditioning to take the place of the overt architectural queues that came before, leaving us seeking some increasingly emancipatory arrangements: that of installation, ephemeral work, performance, et cetera.

Perhaps most tellingly, one of the standouts of the Constructivist theatre movement was Laszlo Moholy-Nagy who famously had a series of enamel paintings fabricated over the phone. John Roberts identified him as being one of the premier examples of an artist engaged in the practice of Surrogacy—a sort of liberated state of the deskilled artist as opposed to Marx’s alienated worker: “The readymade, copying without copying, the craft of reproducibility are sites where authorship is remade, and the hand repositioned, and not the places where its expressive functions are finally dissolved…Surrogacy is the name we might give, therefore, to the technical extension of authorship, rather than its deferment or eradication.” A lot of my practice is about trying to consciously use degrees of surrogacy as a means of reflecting back on conditions of labor and authorship, so I find this sort of through line from props to surrogacy to be a useful frame.

Recently I read a great piece by Paul Soulellis in which he argued that printed matter from the web trafficked in a similar Duchampian concept: that of the infra-thin, which is itself indefinable but means to express “the immeasurable gap between two things as they transition or pass into one another” — like a warm seat or the differences between editions of a print. He argues that when holding a printed document from the web you’re feeling some ephemeral trace of the network, but retaining the satisfaction of the physical object. This particular project comes from the reverse situation, in which the overtly physical qualities of the texts (end pages, spines, dog-ears) ideally frustrates and intrigues in equal measure as it finds itself onto the web. This places the emphasis back on the material rather than the condition of its distribution, and the infra-thin is not web-residue or network-dust but old fashioned tactility.

So here we have a two-fold condition—that of the surrogate work, that is things made with external conditions or hands, and that of the infra-thin—transitory stuff, imbued with traces of performativity. I mean, arguably anybody really interrogating their materials winds up working in a kind of performative way.

There is definitely that aspect of performativity in a lot of work that I’m drawn too. I was speaking with the artist Lina Viste Grønli earlier this year and she summed it up nicely when she said that for her, performance entered her sculptural practice through “the idea that the sculpture or object contained something of the act of making it.” I like this idea that the processes and conditions which led to an objects creation are somehow visible within the finished product. I think artists can employ this as a strategy to both offer audiences new entry points into the work, but also at times to inject a certain levity into the piece. What role does humor play in your practice?

Humour crosscuts the majority of my practice. It has been a valuable framing tool to approach a lot of the ideas I work with. Some of these ideas perhaps only seem humorous in the studio, while others are designed to be humorous in their display. Sometimes I feel like a hapless, slapstick-era protagonist, who are often portrayed as a sort of pathetic everyman of the working class, bumbling through his projects. In many ways this was a sort of performative caricature that I’ve inhabited for the entirety of my All Thumbs series, in which the sculpture is collapsed into the practical—a sort of accidental art (Incidentally, I love the kinds of jobs that Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplain, Laurel & Hardy, and The Stooges seemed to have: low paying and impossibly dangerous labour—itself a kind of parody of work scarcity and deskilled conditions). Humour has always seemed to be an arm of the avant-garde and the marginalized alike.

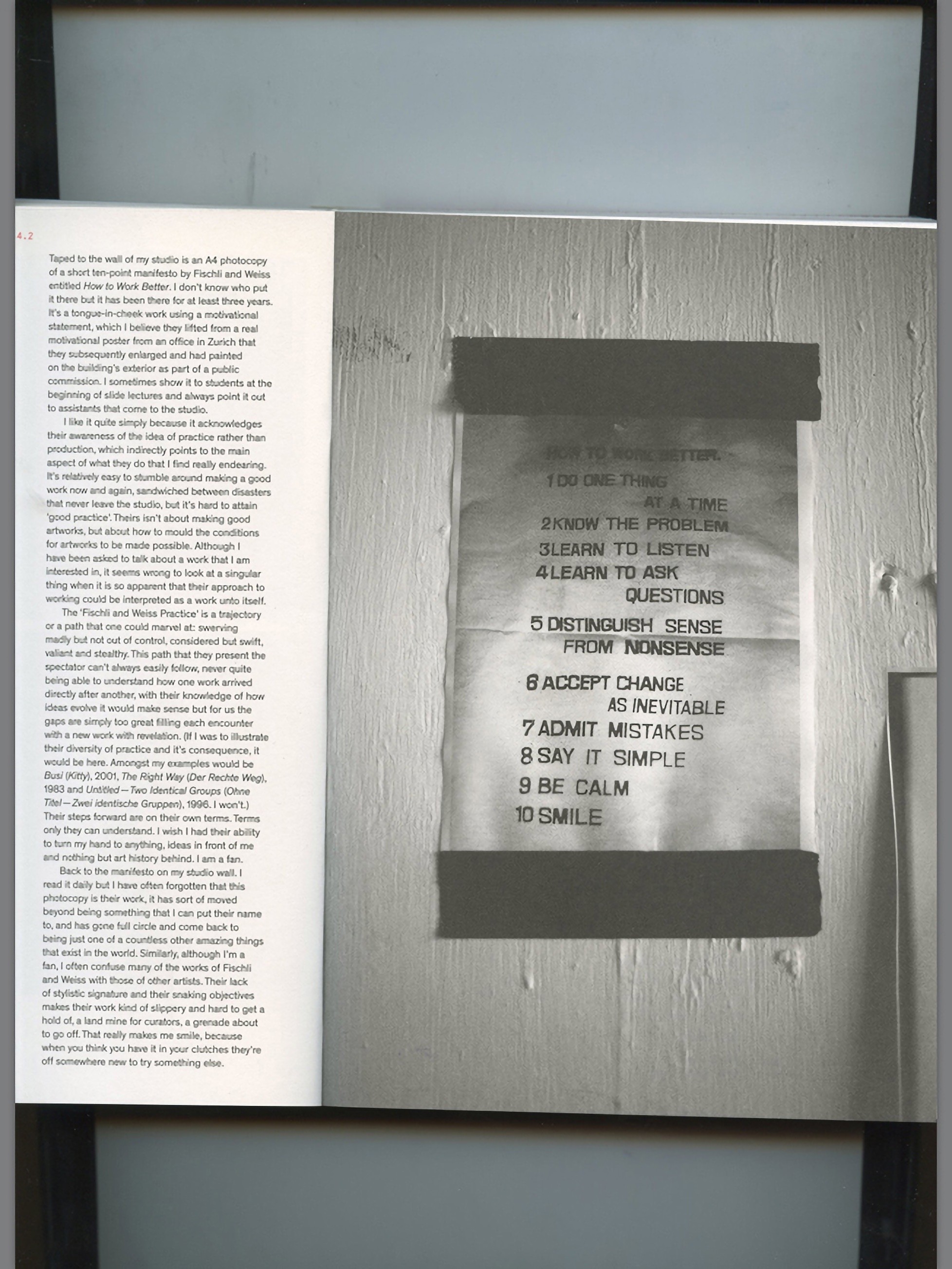

In the reader there’s a section where Mike Kelley talks a bit about post-minimalism and how emancipatory it was to bring these rigid objects into the messy and humorous realm of the body. Coming back to Lina’s statement, I like that it effectively points towards the performative moment in sculpture as a gestural one. Evidence of the artist’s hand—surrogate or otherwise—is embedded somehow in either direct or perhaps auratic terms. Given those terms, we can see the gesture as being something innately human imposed on an object, and broadly I think humour addresses a lot of the complexity of that relationship. I like the idea of turning to humour to push your work or give you an avenue to explore something new.

Humour can also be a crutch to avoid confronting certain realities, so it is very important for me that I’m being absolutely sincere at the same time. Seriously funny, as it were.

This is where my historical interest in the development of funny art comes from: from Irreverent Post-Internet lolz, back through Conceptual and Pop-Art, Situationists, Dada, Caricature, early printing press chapbooks and so on. Ultimately I suppose I flip flop between taking this serious, academic look at the functional role of laughing with or at art, and at actually just laughing my ass off in the studio and hoping some of it comes across to the viewer. I try to have fun.

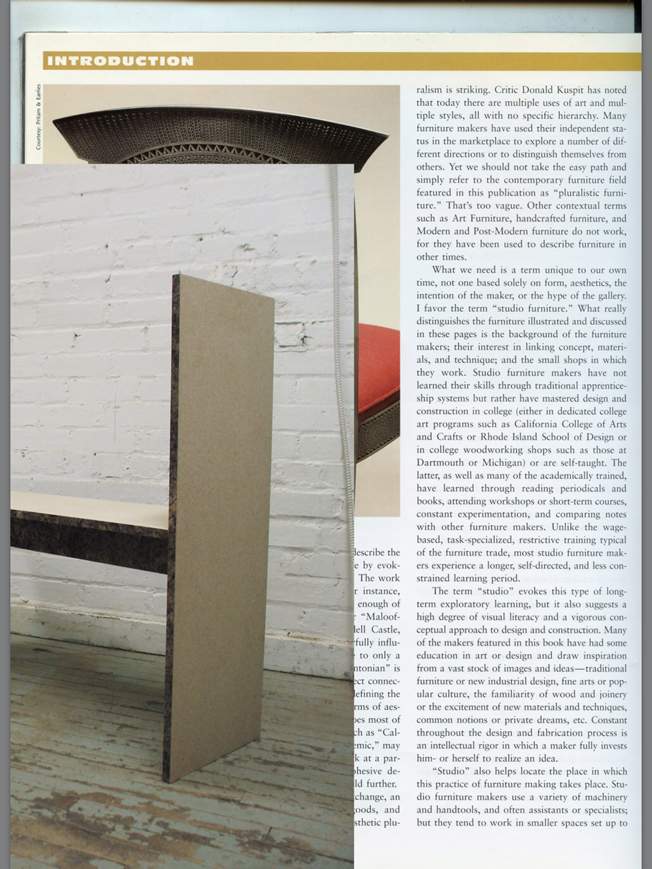

In the past, you’ve created library carts, bookshelves, and dust jackets. You’ve explored books as sculpture, and have produced a series of course readers. I want to finish this conversation by circling back around and asking what may seem like the most obvious question. What is the role of the book in your practice?

Using books as material always seemed like an obvious choice in my practice, and there are probably as many reasons as there are projects for why I gravitate to them. The book has gone through an interesting shift as a cultural good, in that it has shed its role as the primary container for information, and taken on more qualities of a boutique object. We get our information from a screen and turn around and organize our bookshelves by colour. I suppose I find this kind of funny, and a bit sad. The net result is that while for me books are still my primary means of consuming any text of significant length, they have also become a very cheap but loaded kind of material to work with. The dust jackets aren’t meant to be necessarily critical of the book-as-fetish-object. In fact, they kind of play into them, though for me it was simply the most appropriate action for books bought by weight or in discounted numbers: to use something that would otherwise go to waste, whether it be the books themselves or the materials that make up the printed collages enveloping them. I do like how, by a small margin, the dust jacket costs more to protect the book than the book itself. I have a strong inclination to work in the multiple - part of it allows for some transparency to see how an idea develops over time and I tend to be better at making a lot of something and editing after the fact.

The idea of tangible information kind of excites me too. There is a lot of emphasis on the tactile experience of reading in the Course Reader as well—a good deal of attention placed on dog-ears, cracked spines, underlined passages and so on. This comes back to simple material honesty on one hand, and a desire to emphasize the alienation one experiences with PDFs. I suppose there’s also a degree of preservation happening as well.

As an art object or subject it feels a bit like I’m trying to get it out of my system, but as a basic pleasure I’d like to spend the rest of my life with these things around me, so it’s hard to know when to stop.